More hospitals and medical practices have begun charging for doctors’ responses to patient queries, depending on the level of medical advice.To Nina McCollum, Cleveland Clinic’s decision to begin billing for some email correspondence between patients and doctors “was a slap in the face.”She has relied on electronic communications to help care for her ailing 80-year-old mother, Penny Cooke, who is in need of specialized psychiatric treatment from the clinic. “Every 15 or 20 dollars matters, because her money is running out,” she said.Electronic health communications and telemedicine have exploded in recent years, fueled by the coronavirus pandemic and relaxed federal rules on billing for these types of care. In turn, a growing number of health care organizations, including some of the nation’s major hospital systems like Cleveland Clinic, doctors’ practices and other groups, have begun charging fees for some responses to more time-intensive patient queries via secure electronic portals like MyChart.Cleveland Clinic said that its email volume had doubled since 2019. But it added that since the billing program began in November, fees had been charged for responses to less than 1 percent of the roughly 110,000 emails a week its providers received.“Billing a patient’s health insurance supports the necessary decision-making and time commitment of our physicians and other advanced professional providers,” said Angela Smith, a spokeswoman for the clinic.But a new study shows that the fees, which some institutions say range from a co-payment of as little as $3 to a charge of $35 to $100, may be discouraging at least a small percentage of patients from getting medical advice via email. Some doctors say they are caught in the middle of the debate over the fees, and others raised concerns about the effects that the charges might have on health equity and access to care.Dr. Eve Rittenberg, an internist in women’s health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, examined the effects of medical correspondence with patients in a study that found that female practitioners shouldered a greater communications burden.“The volume of messaging combined with the expectation of quick turnaround is very stressful,” Dr. Rittenberg said. She recalled one day when she took her teenage daughter to the doctor but was distracted by responding to patient messages on her phone. She recently reduced her clinic schedule — and took a commensurate pay cut — to free up a few hours outside of office visits to cope with other tasks like patient messages.The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services first introduced Medicare billing codes in 2019 that allowed providers to seek reimbursement for writing messages through secure portals. The pandemic prompted the agency to broaden coverage for telemedicine and hospitals significantly expanded its overall use.The federal rules state that a billable message must be in response to a patient inquiry and require at least five minutes of time, effectively making it a virtual visit. Private insurers have widely followed Medicare’s lead, reimbursing health care practices for physicians’ emails, and may charge patients a co-pay. For several major hospital systems across the country, the increase in email fees has opened up a new revenue stream.More on the Coronavirus PandemicAnnual Boosters: The Food and Drug Administration proposed that most Americans be offered a single dose of a Covid vaccine each fall, much as they are given flu shots.A Better Covid Winter: Some of the worst days of Covid in the United States have come as winters have settled in. But a surge in hospitalizations has yet to materialize this season.New Subvariant: A highly contagious version of the Omicron variant — known officially as XBB.1.5 or by its subvariant nickname, Kraken — is quickly spreading in the United States.Pfizer’s Boosters: Federal officials said that fears that the Covid booster shots made by Pfizer may increase the risk of strokes in people aged 65 and older were not borne out by an intensive scientific investigation.Blue Cross Blue Shield said some of its state and regional plans reimburse for doctor emails. But David Merritt, a senior vice president for policy and advocacy for the insurer, expressed concern that the ability “to charge patients for what often should be routine email follow-up could easily be viewed and abused as a new revenue stream.”According to the Cleveland Clinic, Medicaid patients are not charged. Medicare beneficiaries without a supplemental health plan would owe a co-pay between $3 and $8. The clinic’s maximum charge, hitting those with high deductibles on private insurance plans or without coverage, would be $33 to $50 for each exchange.Ms. McCollum and other clinic patients are given the option of avoiding such fees by choosing to discontinue a query or request an appointment instead. Ms. McCollum kept on emailing on behalf of her mother: “I said, ‘Yes,’ because I need to reach her doctor.” She added, “It’s maddening.”“The volume of messaging combined with the expectation of quick turnaround is very stressful,” said Dr. Eve Rittenberg, an internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She recently reduced her schedule to accommodate a few hours for patient messages.Sophie Park for The New York TimesNot all patient-doctor exchanges carry fees. Emails for simpler concerns largely remain free, including for prescription refills, appointment scheduling and follow-up care. According to several hospital systems and insurers, electronic communications that could prompt a bill would address, for example, medication changes, a new medical issue or symptom or shifts in long-term health conditions. Providers may only bill a patient once a week.Nearly a dozen of the nation’s largest hospital systems said they charged fees for some of their providers’ emails to patients or have started pilot programs, in response to an informal survey by The New York Times. In addition to Cleveland Clinic, this includes Houston Methodist; NorthShore University HealthSystem, Lurie Children’s, and Northwestern Medicine in Illinois; Ohio State University; Lehigh Valley Health Network in Pennsylvania; Oregon Health & Science University; University of California, San Francisco and U.C. San Diego; and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.Other major hospitals are closely watching those at the vanguard of this new billing practice, according to A Jay Holmgren, an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at U.C.S.F.The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) permits doctors to send unencrypted emails or texts if they caution patients about the risks of unsecure channels. But to protect patient privacy, prevent hacking and comply with other HIPAA requirements, most health care companies and organizations discourage the use of anything other than the encrypted portals like MyChart that have become ubiquitous over the past decade.Hospital officials note that while young people may be the most tech-savvy and wedded to app-based correspondence, they are usually healthier and less apt to keep in touch with their doctors.“In my own experience, most messages come from individuals in their 50s and 60s, likely because they are sufficiently familiar with technology to learn how to use messaging and are starting to have increasing needs, whether screening or illness-related,” said Dr. Daniel R. Murphy, an internist and chief quality officer at Baylor Medicine in Houston, which does not currently bill for emails.Before the pandemic, Dr. Murphy found in his research that primary care doctors spent about an hour a day managing their inbox. But a recent study led by Dr. Holmgren of data from Epic, a dominant electronic health records company, showed that the rate of patient emails to providers had increased by more than 50 percent in the last three years.“We’re at an inflection point with messaging,” Dr. Holmgren said. “How are we going to deliver care in the future as we continuously move away from all care being a discrete visit?”Many doctors and their assistants have little time during work hours for replying to patients. Doctors find themselves attending to such demands during “pajama time” before bed, according to Dr. Anthony Cheng, an associate professor of family medicine at Oregon Health & Science.“We know that this is a contributor to burnout,” Dr. Rittenberg said. “Burnout and resulting attrition in physicians’ work is becoming a crisis in our medical system.”Dr. Rittenberg teamed up with her husband, Jeffrey B. Liebman, an economist at the Harvard Kennedy School, to study electronic health record responsibilities among primary care doctors at Brigham. In an article published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in January 2022, they reported that female doctors spent more time responding to messages and received more messages from both patients and staff members than their male colleagues. This difference, they surmised, could help explain greater burnout rates among women in medicine.Some doctors have reported examples of patients who communicate too frequently or insistently through the online portal.“People now have the expectation that these communications are like texts and that they should get a response right away,” Dr. Rittenberg said. But, she said she empathized with what might be driving such patients’ insistent inquiries: pandemic-era malaise.“People are very anxious and worried and isolated, and the doctor offers a connection,” she said.Attaching a monetary fee to doctor-patient emails may be a step toward recognition of the value of this particular practice. But the addition of another bill has primed simmering resentments among some Americans, who are experiencing “pandemic fatigue” and have strained household budgets because of inflation, including higher health care costs.Ms. McCollum, a marketing writer, has been trying to raise extra cash to help cover her mother’s care by selling some of Ms. Cooke’s belongings online.“It’s been a tough year and I don’t need the clinic making it any worse,” she added.Dr. Kedar Mate, chief executive at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, a nonprofit in Boston, said charging for providers’ emails amounted to “a very complicated and slippery slope” and that it could exacerbate health inequities.“Increasing levels of communication and interactions with patients is a good thing,” Dr. Mate said. “And I worry about disincentivizing that by creating a financial barrier.”“Increasing levels of communication and interactions with patients is a good thing,” said Kedar Mate, chief executive at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.Carlos Bernate for The New York TimesCaitlin Donovan, senior director of the Patient Advocate Foundation, said that even a small co-pay could prove alienating to people living paycheck to paycheck.“We write a lot of $5 checks in this organization,” she said, referring to subsidies for co-pays and other out-of-pocket medical expenses.Others pointed out that when a severe physician shortage left patients waiting months to see a specialist, exchanging messages was a time-efficient way to bridge those gaps.“It’s really been a win-win for our physicians and our patients,” said LeTesha Montgomery, senior vice president for system patient access at Houston Methodist, which rolled out a full billing plan beginning in September. “So, it actually helped us increase access for our patients,” she said.Some patients view billing for a provider’s time and expertise as only fair and a good use of their own time, as well.Kacie Lewis, 29, is among those who manage their health concerns electronically. Until recently, her Aetna insurance coverage had a high deductible, through her work as a product manager at a health care company. And since late 2021, she said, she had been billed $32 for each of three email threads, seeking treatments for psoriasis, eczema and a yeast infection from providers at Novant Health in Charlotte, N.C.“Time is money,” Ms. Lewis said. “And to be able to submit something super simple and communicate with your doctor over email is much better than driving 20 minutes one way, 20 minutes back the other way and potentially sitting in the waiting room.”In a paper published on Jan. 6 in JAMA, Dr. Holmgren and his colleagues reported that after U.C.S.F. Health started its email billing in November 2021, there was a slight drop in the number of patient emails to providers. The researchers suggested that might have been the result of patients’ reluctance to be charged a fee.In the first year, U.C.S.F. billed for 13,000 message threads, or about 1.5 percent of 900,000 threads and more than three million messages, according to the study. (Other hospitals told The Times they billed for no greater than 2 percent of threads.) From about $20 from Medicare and Medicaid and $75 from commercial insurers per bill, the email fees generated $470,000, compared with the system’s $5.6 billion in 2021 revenues.“This will hopefully be revenue-neutral,” Dr. Holmgren said. “We are not intending to make this a profitable enterprise.”Critics argue that billing for a small fraction of emails is not likely to reduce physician burnout substantially unless hospitals also set aside workday hours for patient queries and reward clinicians for those efforts. U.C.S.F. has begun giving “productivity points,” a metric used for compensation, for doctors’ correspondence.Jack Resneck Jr., president of the American Medical Association, said he supported insurance coverage for emailing as a way to adjust health care models to fast-changing times.“How do we reinvent the physician’s day and the care delivery system to actually recognize and support the broad array of ways that we deliver care?” Dr. Resneck asked.

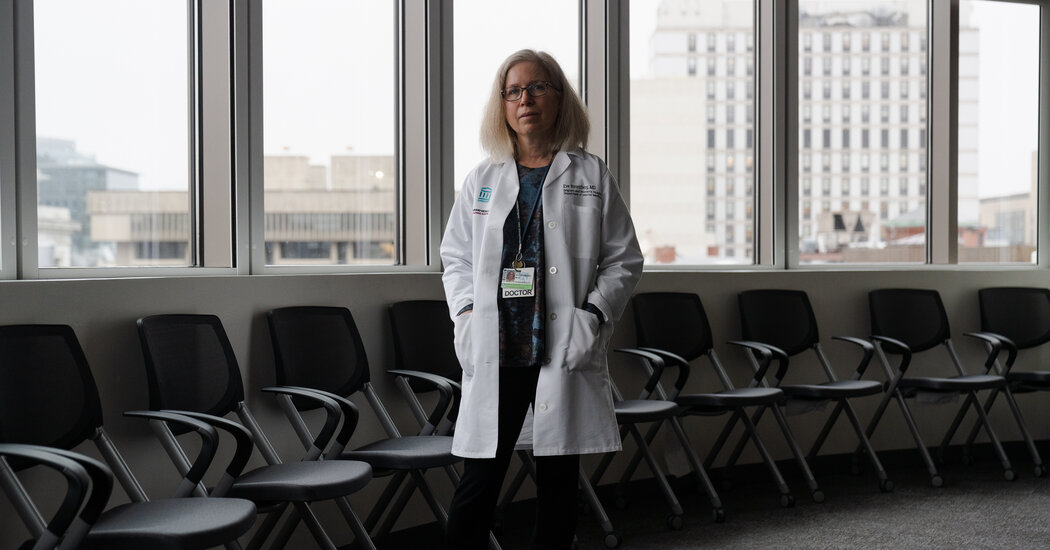

Read more →