Moderna vs. Pfizer: Both Knockouts, but One Seems to Have the Edge

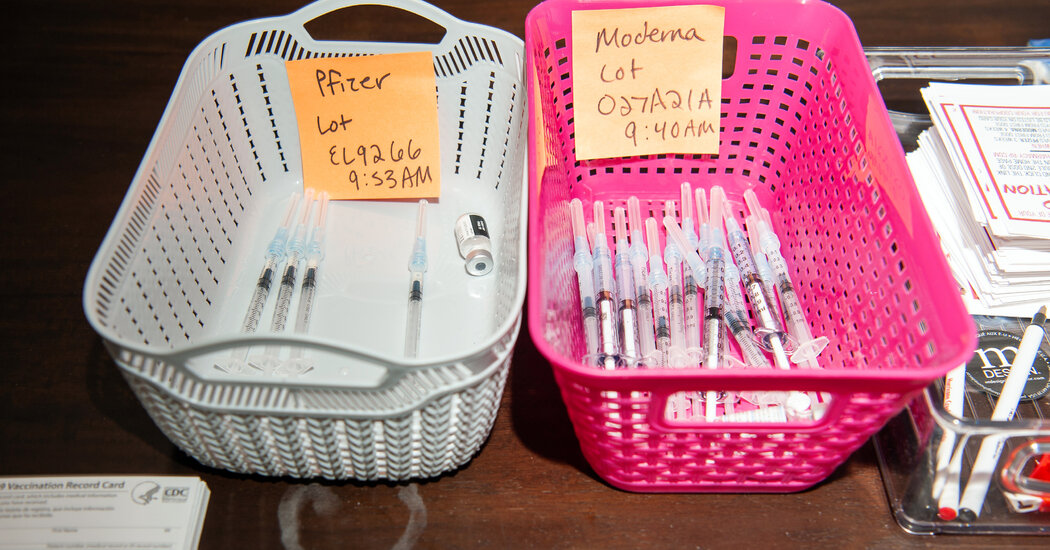

A series of studies found that the Moderna vaccine seemed to be more protective over the long term than the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Here’s why.It was a constant refrain from federal health officials after the coronavirus vaccines were authorized: These shots are all equally effective.That has turned out not to be true.Roughly 221 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine have been dispensed thus far in the United States, compared with about 150 million doses of Moderna’s vaccine. In a half-dozen studies published over the past few weeks, Moderna’s vaccine appeared to be more protective over the long term than the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.Research published on Friday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that the efficacy of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine against hospitalization fell from 91 percent to 77 percent after a four-month period following the second shot. The Moderna vaccine showed no decline over the same period.If the efficacy gap continues to widen, it may have implications for the debate on booster shots. Federal agencies this week are evaluating the need for a third shot of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for some high-risk groups, including older adults.Scientists who were initially skeptical of the reported differences between the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines have slowly become convinced that the disparity is small but real.“Our baseline assumption is that the mRNA vaccines are functioning similarly, but then you start to see a separation,” said Natalie Dean, a biostatistician at Emory University in Atlanta. “It’s not a huge difference, but at least it’s consistent.”But the discrepancy is small and the real-world consequences uncertain, because both vaccines are still highly effective at preventing severe illness and hospitalization, she and others cautioned.“Yes, likely a real difference, probably reflecting what’s in the two vials,” said John Moore, a virologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “But truly, how much does this difference matter in the real world?”“It’s not appropriate for people who took Pfizer to be freaking out that they got an inferior vaccine.”Even in the original clinical trials of the three vaccines eventually authorized in the United States — made by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson — it was clear that the J.&J. vaccine had a lower efficacy than the other two. Research since then has borne out that trend, although J.&J. announced this week that a second dose of its vaccine boosts its efficacy to levels comparable to the others.The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines rely on the same mRNA platform, and in the initial clinical trials, they had remarkably similar efficacy against symptomatic infection: 95 percent for Pfizer-BioNTech and 94 percent for Moderna. This was in part why they were described as more or less equivalent.The subtleties emerged over time. The vaccines have never been directly compared in a carefully designed study, so the data indicating that effects vary are based mostly on observations.Results from those studies can be skewed by any number of factors, including the location, the age of the population vaccinated, when they were immunized and the timing between the doses, Dr. Dean said.For example, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was rolled out weeks before Moderna’s to priority groups — older adults and health care workers. Immunity wanes more quickly in older adults, so a decline observed in a group consisting mostly of older adults may give the false impression that the protection from the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine falls off quickly.Given those caveats, “I’m not convinced that there truly is a difference,” said Dr. Bill Gruber, a senior vice president at Pfizer. “I don’t think there’s sufficient data out there to make that claim.”But by now, the observational studies have delivered results from a number of locations — Qatar, the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, several other states in the United States — and in health care workers, hospitalized veterans or the general population.Moderna’s efficacy against severe illness in those studies ranged from 92 to 100 percent. Pfizer-BioNTech’s numbers trailed by 10 to 15 percentage points.The two vaccines have diverged more sharply in their efficacy against infection. Protection from both waned over time, particularly after the arrival of the Delta variant, but the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine’s values fell lower. In two of the recent studies, the Moderna vaccine did better at preventing illness by more than 30 percentage points.A few studies found that the levels of antibodies produced by the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine were one-third to one-half those produced by the Moderna vaccine. Yet that decrease is trivial, Dr. Moore said: For comparison, there is a more than 100-fold difference in the antibody levels among healthy individuals..css-1xzcza9{list-style-type:disc;padding-inline-start:1em;}.css-3btd0c{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:1rem;line-height:1.375rem;color:#333;margin-bottom:0.78125rem;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-3btd0c{font-size:1.0625rem;line-height:1.5rem;margin-bottom:0.9375rem;}}.css-3btd0c strong{font-weight:600;}.css-3btd0c em{font-style:italic;}.css-w739ur{margin:0 auto 5px;font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.125rem;line-height:1.3125rem;color:#121212;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-family:nyt-cheltenham,georgia,’times new roman’,times,serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.375rem;line-height:1.625rem;}@media (min-width:740px){#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-size:1.6875rem;line-height:1.875rem;}}@media (min-width:740px){.css-w739ur{font-size:1.25rem;line-height:1.4375rem;}}.css-9s9ecg{margin-bottom:15px;}.css-16ed7iq{width:100%;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;justify-content:center;padding:10px 0;background-color:white;}.css-pmm6ed{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}.css-pmm6ed > :not(:first-child){margin-left:5px;}.css-5gimkt{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:0.8125rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-letter-spacing:0.03em;-moz-letter-spacing:0.03em;-ms-letter-spacing:0.03em;letter-spacing:0.03em;text-transform:uppercase;color:#333;}.css-5gimkt:after{content:’Collapse’;}.css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;-webkit-transform:rotate(180deg);-ms-transform:rotate(180deg);transform:rotate(180deg);}.css-eb027h{max-height:5000px;-webkit-transition:max-height 0.5s ease;transition:max-height 0.5s ease;}.css-6mllg9{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;position:relative;opacity:0;}.css-6mllg9:before{content:”;background-image:linear-gradient(180deg,transparent,#ffffff);background-image:-webkit-linear-gradient(270deg,rgba(255,255,255,0),#ffffff);height:80px;width:100%;position:absolute;bottom:0px;pointer-events:none;}.css-uf1ume{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-box-pack:justify;-webkit-justify-content:space-between;-ms-flex-pack:justify;justify-content:space-between;}.css-wxi1cx{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:column;-ms-flex-direction:column;flex-direction:column;-webkit-align-self:flex-end;-ms-flex-item-align:end;align-self:flex-end;}.css-12vbvwq{background-color:white;border:1px solid #e2e2e2;width:calc(100% – 40px);max-width:600px;margin:1.5rem auto 1.9rem;padding:15px;box-sizing:border-box;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-12vbvwq{padding:20px;width:100%;}}.css-12vbvwq:focus{outline:1px solid #e2e2e2;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-12vbvwq{border:none;padding:10px 0 0;border-top:2px solid #121212;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transform:rotate(0deg);-ms-transform:rotate(0deg);transform:rotate(0deg);}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-eb027h{max-height:300px;overflow:hidden;-webkit-transition:none;transition:none;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-5gimkt:after{content:’See more’;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-6mllg9{opacity:1;}.css-qjk116{margin:0 auto;overflow:hidden;}.css-qjk116 strong{font-weight:700;}.css-qjk116 em{font-style:italic;}.css-qjk116 a{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;text-underline-offset:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-thickness:1px;text-decoration-thickness:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:visited{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}Still, other experts said that the corpus of evidence pointed to a disparity that would be worth exploring, at least in people who respond weakly to vaccines, including older adults and immunocompromised people.“At the end of the day, I do think there are subtle but real differences between Moderna and Pfizer,” Dr. Jeffrey Wilson, an immunologist and physician at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville who was a co-author of one such study, published in the journal JAMA this month. “In high-risk populations, it might be relevant. It’d be good if people took a close look.”“Pfizer is a big hammer,” Dr. Wilson added, but “Moderna is a sledgehammer.”Several factors might underlie the divergence. The vaccines differ in their dosing and in the time between the first and second doses.Vaccine manufacturers would typically have enough time to test a range of doses before choosing one — and they have done such testing for their trials of the coronavirus vaccine in children.But in the midst of a pandemic last year, the companies had to guess at the optimal dose. Pfizer went with 30 micrograms, Moderna with 100.Moderna’s vaccine relies on a liquid nanoparticle, which can deliver the larger dose. And the first and second shots of that vaccine are staggered by four weeks, compared with three for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.The extra week may give immune cells more time to proliferate before the second dose, said Dr. Paul Burton, Moderna’s chief medical officer. “We need to keep studying this and to do more research, but I think it’s plausible.”Moderna’s team recently showed that a half dose of the vaccine still sent antibody levels soaring. Based on those data, the company asked the F.D.A. this month to authorize 50 micrograms, the half dose, as a booster shot.There is limited evidence showing the effect of that dose, and none on how long the higher antibody levels might last. Federal regulators are reviewing Moderna’s data to determine whether the available data are sufficient to authorize a booster shot of the half dose.Ultimately, both vaccines are still holding steady against severe illness and hospitalization, especially in people under 65, Dr. Moore said.Scientists had initially hoped that the vaccines would have an efficacy of 50 or 60 percent. “We would have all seen that as great result and been happy with it,” he said. “Fast forward to now, and we’re debating whether 96.3 percent vaccine efficacy for Moderna versus 88.8 percent for Pfizer is a big deal.”

Read more →