One patent application for psilocybin therapy claimed its treatment rooms were unique because they featured “muted colors,” high-fidelity sound systems and cozy furniture. Another sought exclusivity on a therapist reassuringly holding the hand of a patient. Then there’s the patent seeking a monopoly on nearly all methods of delivering the drug to patients, including vaginally and rectally.Humans have been consuming psilocybin, or “magic,” mushrooms for millenniums, and most synthetic hallucinogens have been around for decades. But as excitement about the promise of psychedelic medicine reaches a fever pitch, drawing hundreds of millions in investment, there is a growing scrum of psychedelic companies seeking to gain a financial edge through a blizzard of patent claims — or at least to scare off potential competitors.The patent application that described therapy room décor and drug delivery methods was filed by Compass Pathways, a psychedelic medicine company valued at $450 million, that, with at least 50 claims, has been especially aggressive with its intellectual property filings. Over the past three years, its competitors have collectively filed more than a hundred applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, some of which have been granted and others rejected.George Goldsmith, the co-founder and executive chairman of Compass, said the company’s patent strategy was necessary to ensure that psilocybin therapy would one day be available to people across the globe. He said that required raising hundreds of millions of dollars to conduct clinical trials at 150 sites in Europe and North America, the key to winning over regulators in multiple countries and for convincing both private and government insurers to cover psychedelic therapies. “It’s hard, tedious work that can’t be done as a philanthropic venture,” he said.Granted developing new drugs, proving their efficacy and safety through clinical trials and then winning approval from regulators is hugely expensive, and patents are often necessary to protect a company’s investment in that process.But the patent claims by Compass and other companies have provoked howls of derision from some scientists and patient advocates, who warn that corporate efforts to profit from existing drugs like psilocybin, LSD and Ecstasy could chill academic research and throttle public access by making new therapies prohibitively expensive.A treatment room of Compass Pathways, which is described in the patent, at King’s College Hospital in London.Tom Jamieson for The New York Times“I’m not anticapitalist or anti-profit making, but I am opposed to patent trolling, which is when you claim you invented something you didn’t invent,” said Carey Turnbull, who founded two psychedelic companies and now runs Freedom to Operate, an advocacy group that has been challenging psychedelic patent claims it views as flawed, including those filed by Compass. The clash over psychedelic-related intellectual property highlights the soaring expectations of investors, philanthropists and researchers who are rushing to shape an emerging field that many believe could revolutionize the treatment of depression, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health conditions.Robin Feldman, an expert on pharmaceutical intellectual property at the University of California Hastings College of Law, said the conflict over psychedelics reflects the larger problems of a patent system that saddles Americans with some of the highest prescription drug prices in the world. “It’s not pretty when you look under the hood,” she said. “With psychedelics, what we’re seeing is a clash of cultures between the altruism of those who want to use existing compounds in new and exciting ways crashing up against the realities of the patent system.”Though most psychedelic drugs remain illegal under federal law, the Food and Drug Administration has become more receptive to new uses for them. The agency is weighing approval of the therapeutic uses of MDMA, better known as Ecstasy, and psilocybin, which is undergoing accelerated review. Three years ago, the F.D.A. approved esketamine, a nasal spray derived from the anesthetic ketamine, for depression that is resistant to other types of treatment.For the first time in decades, the National Institutes of Health has begun funding psychedelic research, and many of the country’s premier universities have been racing to set up psychedelic research centers. A number of them have also entered into partnerships with drug companies, which are seeking to patent new therapies — and share any future profits.Seattle, Denver, Oakland, Calif., and Washington, D.C. are among a score of municipalities that have decriminalized psilocybin mushrooms. In January, Oregon will become to first state to offer psilocybin therapy in a clinical setting.Investment has been pouring into the three dozen publicly listed companies — most of which didn’t exist four years ago. According to InsightAce Analytic, a market research firm, the psychedelic therapeutics market was worth $3.6 billion in 2021 and is expected to reach $8.3 billion by 2028, though many companies, like their biotech start-up cousins and the overall market, have been buffeted by declining stock prices in recent months.“It feels like it came out of nowhere with a very powerful, attention-grabbing debut,” said Ritu Baral, an analyst who follows the psychedelics sector for the investment bank Cowen.The shifting terrain is bracing for veteran psychedelic researchers who kept the flame alive during the nation’s concerted war on drugs, when funding evaporated. On one hand, they are thrilled by the gush of promising new studies, positive media coverage and unexpected support from conservative politicians moved by the stories of traumatized combat veterans healed by psychedelic-assisted therapy.A lab-grown Psilocybe mushroom in Canada.Alana Paterson for The New York TimesBut like many longtime researchers, Robert Jesse, who helped start the psilocybin research division at Johns Hopkins University over two decades ago, sees potential pitfalls. To him, psychedelics are spiritual tools that belong to all of humanity, not just those wealthy enough to afford a $5,000 psychedelic retreat.“While I’m not a conventionally religious person, my early experiences with psychedelics changed my worldview in religious ways,” said Mr. Jesse, who in 2005 filed an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of a religious group that was seeking to import the natural hallucinogenic ayahuasca for its ceremonies. The court ruled unanimously in the group’s favor.Mr. Jesse said corporatization threatens to take the psychedelic field in potentially troubling directions. The surge of money is luring away talented scientists from research at academic institutions. The promise of hefty returns for investors, he and other experts have said, has also led to a decline in the philanthropic largess that has sustained psychedelic research in recent years.But it’s the flood of patent filings that most worries Mr. Jesse, given the time and the millions of dollars it can take to fight a patent claim, even one that a court eventually dismisses as meritless. “It’s a scorched-earth approach, in that a company can generate intellectual property that scares others from entering the field,” he said.Mr. Goldsmith, the Compass executive, looks visibly pained when he hears such criticisms. In a video interview, he spoke about why he and his wife started the company: their frustration over the failure of existing drugs to treat their college-age son when he was struggling with depression. “Do we try to change the system, or do we try to help those people in an imperfect system?” Mr. Goldsmith asked. “We chose the latter.”The company’s patent strategy, Mr. Goldsmith said, has been instrumental in coaxing more than $400 million from investors, among them the PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel. Compass is headquartered in London, though its stock trades on the Nasdaq.Other drug company executives disputed the idea that patent filings were cynical attempts to gain a monopoly over existing drugs. Doug Drysdale, the chief executive of Cybin, a three-year-old psychedelics company based in Canada, said patents protect the work of scientists trying to enhance the therapeutic value of existing drugs.He cited DMT, or dimenthyltryptamine, a naturally occurring hallucinogen known to produce intense experiences. The problem, he said, is that they are notably brief, sometimes lasting just five minutes to 10 minutes — perhaps not quite long enough to disrupt ingrained ways of thinking and help people with severe depression find new ways to apprehend their illness.Mr. Drysdale said the company had recently obtained a patent for an altered version of DMT that opened up the possibility of sessions lasting 30 minutes to 40 minutes. “It’s not modifying the molecule for modification’s sake,” he said. “If you’re asking investors for hundreds of millions of dollars, you need to have the intellectual property, otherwise there’s no way to get a return on investment.”A number of companies, including Cybin, have been working to create psilocybin analogues that produce experiences lasting two to three hours, roughly half the time required for the current therapy. Here, the goal is to lower the cost of treatment, given that many psychedelic sessions require the participation of two licensed professionals, a safeguard against potential patient abuse that markedly increases costs.Robert Jesse, who has studied psilocybin for twenty years, worried about the surge of patent filings. “It’s a scorched-earth approach,” he said.Brian L. Frank for The New York TimesDr. Stephen Ross, a founding member of New York University’s Psychedelic Research Group, said he feared that efforts to create much shorter psychedelic episodes without requiring psychotherapy could lead to bad experiences for patients and negative media attention, potentially spurring the kind of backlash that strangled the nascent field four decades ago during the nation’s war on drugs. “It could completely destroy all the progress of the past few years,” he said.In some ways, the business model for psychedelics is deeply problematic, analysts say. Most psychedelic therapies are based on just a handful of sessions, a potential obstacle to big profits. By contrast, many of the most lucrative drugs on the market — like those that treat diabetes, hypertension or kidney failure — are taken over the course of a lifetime.Psychedelic medicine is also complicated in another way: Most researchers are not seeking F.D.A. approval for the compounds alone, but rather for a package that pairs the drugs with talk therapy.The therapy, which often includes preparing patients for taking the drugs and helping them process the experience, is key to successful treatment, researchers say. Giving short shrift to it or overlooking the mind-set of the patient and the place where the sessions take place can lead to bad trips, especially for those with pre-existing psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.Dr. Yvan Beaussant, a palliative care specialist at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute who has been studying psilocybin therapy for terminally ill patients, said that he worried the profit-driven model of drug development would shortchange psychotherapy.He and other researchers say they struggle to obtain grant money for clinical trials to determine the kind of talk therapy that works best. “Psychotherapy is not where the profit is for these companies,” he said.For now, the effort to rein in excessive patent claims is led by a group of four dozen intellectual property wonks and archivists who volunteer to trawl university libraries and scour long-forgotten research papers. Their database, Porta Sophia, or “Doorway to Wisdom,” aims to help U.S. patent officials assemble what’s known as “prior art,” evidence about a drug or therapy that has been overlooked or lost to time that patent examiners can use to reject a flawed or excessively broad patent application.David Casimir, a patent lawyer who started Porta Sophia, said that much of the earlier research on psychedelics was done before the advent of electronic databases, much of it by researchers who abandoned the field amid the government crackdown of the 1970s and 1980s.“We’re talking about sources of information that would be challenging for a patent reviewer to find on their own,” said Mr. Casimir, who began the project two years ago after becoming alarmed by what he saw as questionable patent claims. “If we’re doing our job correctly, the worst, most egregiously overreaching patents will have prior art available on our website for examiners to find.”In some cases, the organization itself challenges patent approvals. Mr. Casimir laughed when recalling one claim by a company that a combination of MDMA and LSD was novel. As any psychedelic aficionado well knows, he said, that combination has been around for decades and is fondly referred to as “candy flipping.”A month after Porta Sophia challenged the application, the company voluntarily scaled back its claims. Earlier this year, Porta Sophia also challenged the claims filed by Compass Pathways, the company that had described room décor and music in its patent application. In August, Compass withdrew the claims.The company, however, is still pursuing them abroad.

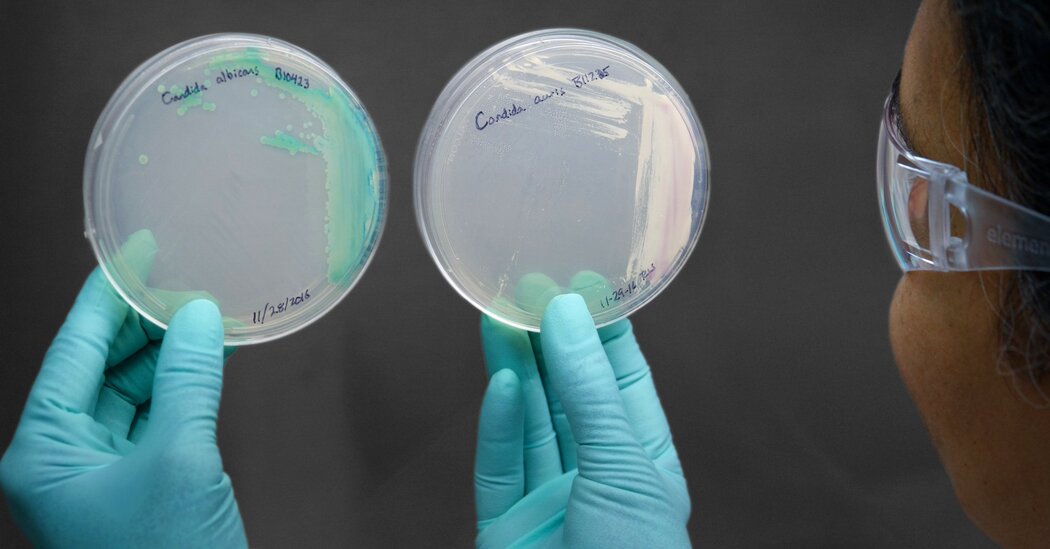

Read more →