Empowering Medicare to negotiate prices directly with drug makers has been a Democratic goal for 30 years, one the pharmaceutical industry has fought ferociously.WASHINGTON — For decades, as prescription drug costs have soared, Democrats have battled with the pharmaceutical industry in pursuit of an elusive goal: legislation that could drive down prices by allowing Medicare to negotiate directly with drug makers.Now they are on the verge of passing a broad budget bill that would do just that, and in the process deliver President Biden a political victory that he and his party can take to voters in November.Empowering Medicare to negotiate prices for up to 10 drugs initially — and more later on — along with several other provisions aimed at lowering health care costs, would be the most substantial change to health policy since the Affordable Care Act became law in 2010, affecting a major swath of the population. It could save some older Americans thousands of dollars in medication costs each year.The legislation would extend, for three years, the larger premium subsidies that low- and middle-income people have received during the coronavirus pandemic to get health coverage under the Affordable Care Act, and allow those with higher incomes who became eligible for such subsidies during the pandemic to keep them. It would also make drug makers absorb some of the cost of medicines whose prices rise faster than inflation.Significantly, it also would limit how much Medicare recipients have to pay out of pocket for drugs at the pharmacy to $2,000 annually — a huge benefit for the 1.4 million beneficiaries who spend more than that each year, often on medicines for serious diseases like cancer and multiple sclerosis.Lower prices would make a huge difference in the lives of people like Catherine Horine, 67, a retired secretary and lung recipient from Wheeling, Ill. She lives alone on a fixed income of about $24,000 a year. Her out-of-pocket drug costs are about $6,000 a year. She is digging into her savings, worried she will run out of money before long.“Two years ago, I was $8,000 in the hole,” she said. “Last year, I was $15,000 in the hole. I expect to be more this year, because of inflation.”Between 2009 and 2018, the average price more than doubled for a brand-name prescription drug in Medicare Part D, the program that covers products dispensed at the pharmacy, the Congressional Budget Office found. Between 2019 and 2020, price increases outpaced inflation for half of all drugs covered by Medicare, according to an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation.The budget office estimates that the bill’s prescription drug provisions will save the federal government $288 billion over 10 years, in part by forcing the pharmaceutical industry to accept lower prices from Medicare for some of its big sellers. Opponents argue that the measure would discourage innovation and cite a new C.B.O. analysis that projects that it would actually lead to higher prices when drugs first come on the market. The Biden PresidencyWith midterm elections looming, here’s where President Biden stands.A Sudden Shift: With progress on major legislation and falling gas prices, President Biden faces the challenge of making those successes resonate.Struggling to Inspire: At a time of political tumult and economic distress, Mr. Biden has appeared less engaged than Democrats had hoped.Low Approval Rating: For Mr. Biden, a pervasive sense of pessimism among voters has pushed his approval rating to a perilously low point.Questions About 2024: Mr. Biden has said he plans to run for a second term, but at 79, his age has become an uncomfortable issue.A Familiar Foreign Policy: So far, Mr. Biden’s approach to foreign policy is surprisingly consistent with the Trump administration, analysts say.Drugs for common conditions like cancer and diabetes that affect older people are most likely to be picked for negotiations. Analysts at the investment bank SVB Securities pointed to the blood thinner Eliquis, the cancer medication Imbruvica and the drug Ozempic, which is given to manage diabetes and obesity, as three of the first likely targets for negotiation.Until recently, the idea that Medicare, which has about 64 million beneficiaries, would be able to use its muscle to cut deals with drug makers was unthinkable. Democrats have been pushing for it since President Bill Clinton proposed his contentious health care overhaul in 1993. The pharmaceutical industry’s fierce lobbying against it has become Washington lore.“This is like lifting a curse,” Senator Ron Wyden, Democrat of Oregon and the architect of the measure, said of the Medicare negotiation provision. “Big Pharma has been protecting the ban on negotiation like it was the Holy Grail.”Senator Ron Wyden is the architect of the drug-price negotiation measure.Haiyun Jiang/The New York TimesDavid Mitchell, 72, is among those who would be helped. A retired Washington, D.C., public relations man, he learned in 2010 that he had multiple myeloma, an incurable blood cancer. He pays $16,000 out of pocket each year for just one of four medicines he takes. He also founded an advocacy group, Patients for Affordable Drugs.“Drugs don’t work if people can’t afford them, and too many people in this country can’t afford them,” Mr. Mitchell said. “Americans are angry and they’re being taken advantage of. They know it.”Still, the measure would not deliver every tool that Democrats would like for reining in prescription drug costs. The negotiated prices would not go into effect until 2026, and even then would apply only to a small fraction of the prescription drugs taken by Medicare beneficiaries. Pharmaceutical companies would still be able to charge Medicare high prices for new drugs.That is a disappointment to the progressive wing of the party; The American Prospect, a liberal magazine, has dismissed the measure as “exceedingly modest.”Prescription drug prices in the United States are far higher than those in other countries. A 2021 report from the RAND Corporation found that drug prices in this country were more than seven times higher than in Turkey, for instance.The pharmaceutical industry spends far more than any other sector to advance its interests in Washington. Since 1998, it has spent $5.2 billion on lobbying, according to Open Secrets, which tracks money in politics. The insurance industry, the next biggest spender, has spent $3.3 billion. Drug makers spread their money around, giving to Democrats and Republicans in roughly equal amounts.At a media briefing last week. Stephen J. Ubl, the chief executive of PhRMA, the drug industry’s main lobbying group, warned that the bill would reverse progress on the treatment front, especially in cancer care — a high priority for Mr. Biden, whose son died of a brain tumor.“Democrats are about to make a historic mistake that will devastate patients desperate for new cures,” Mr. Ubl said, adding, “Fewer new medicines is a steep price to pay for a bill that doesn’t do enough to make medicines more affordable.”But Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, said he believed the measure would spur innovation, by “encouraging investment in important new products rather than encouraging pharmaceutical companies to try to keep pushing the same product and delaying generic entry as long as possible.”President Bill Clinton proposed a contentious health care overhaul in 1993. Doug Mills/Associated PressIn 1999, after his health care plan failed, Mr. Clinton resurrected the idea of Medicare prescription drug coverage. But this time, instead of proposing that Medicare negotiate with companies, he suggested leaving that to the private sector.“At that point, what we were trying to do was to accommodate the recognition that Republicans were lockstep in opposition to any type of government role,” said Tom Daschle, the former Senate Democratic leader.But it took a Republican president, George W. Bush, and a Republican Congress to push the prescription drug benefit over the finish line.Medicare Part D, as the benefit is known, had the backing of the drug industry for two reasons: The companies became convinced they would gain millions of new customers, and the bill contained a “noninterference clause,” which explicitly barred Medicare from negotiating directly with drug makers. Repealing that clause is at the heart of the current legislation.The architect of the benefit was a colorful Louisiana Republican congressman, Billy Tauzin, who led the House Energy and Commerce committee at the time. In Washington, Mr. Tauzin is best remembered as an example of the drug industry’s influence: He left Congress in January 2005 to run PhRMA, drawing accusations that he was being rewarded for doing the companies’ bidding — an accusation Mr. Tauzin insists is a false “narrative” created by Democrats to paint Republicans as corrupt.Joel White, a Republican health policy consultant who helped write the 2003 law that created Medicare Part D, said the program was designed for private insurers, pharmacy benefit managers and companies that already negotiate rebates for Medicare plan sponsors to use their leverage to drive down prices.“The whole model was designed to promote private competition,” he said.In the years since Medicare Part D was introduced, polling has consistently found that a vast majority of Americans from both parties want the federal government to be allowed to negotiate drug prices. Former President Donald J. Trump embraced the idea, though only during his campaign.President Biden is on the verge of being able to sign legislation that could save older Americans thousands of dollars in medication costs annually.Tom Brenner for The New York TimesThe new legislation targets widely used drugs during a specific phase of their existence — when they have been on the market for a number of years but still lack generic competition. The industry has come under criticism for deploying strategies to extend the patent period, like slightly tweaking drug formulas or reaching “pay for delay” deals with rival manufacturers to postpone the arrival of cheap generics and “biosimilars,” as the generic versions of biotechnology drugs are called.The drug maker AbbVie, for instance, piled up new patents to maintain a monopoly on its blockbuster anti-inflammatory medicine Humira — and it has reaped roughly $20 billion a year from the drug since its main patent expired in 2016.Ten drugs would qualify for negotiation in 2026, with more added in subsequent years. The bill outlines criteria by which the drugs would be chosen, but the ultimate decision would rest with the health secretary — a provision that Mr. White, the Republican consultant, warned would lead to “an incredible lobbying campaign” to get drugs on the list or keep them off it.Analysts say the bill would hurt drug makers’ bottom lines. Analysts at the investment bank RBC Capital Markets estimated that most companies affected by the measure would bring in 10 to 15 percent less revenue annually by the end of the decade.But while PhRMA has warned that a decline in revenue will make drug makers less willing to invest in research and development, the Congressional Budget Office projected that only 15 fewer drugs would reach the market over the next 30 years, out of an estimated 1,300 expected in that time.The Senate is expected to take up the bill as early as Saturday, then send it to the House. If it passes, as expected, it will pierce the drug industry’s aura of power in Washington, opening the door for more drugs to become subject to negotiations, said Leslie Dach, founder of Protect Our Care, an advocacy group.“Once you lose your invincibility,” he said, “it’s a lot easier for people to take the next step.”

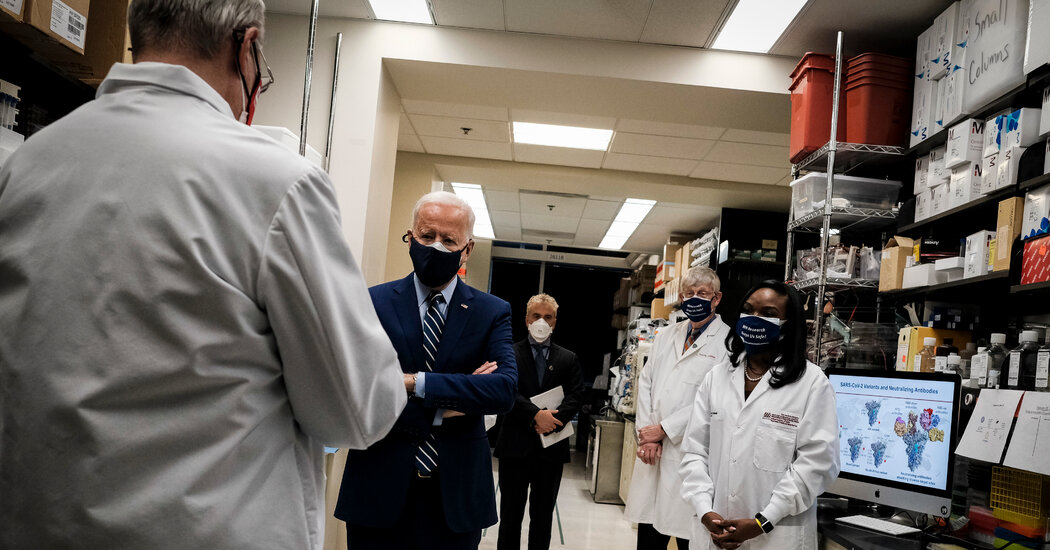

Read more →