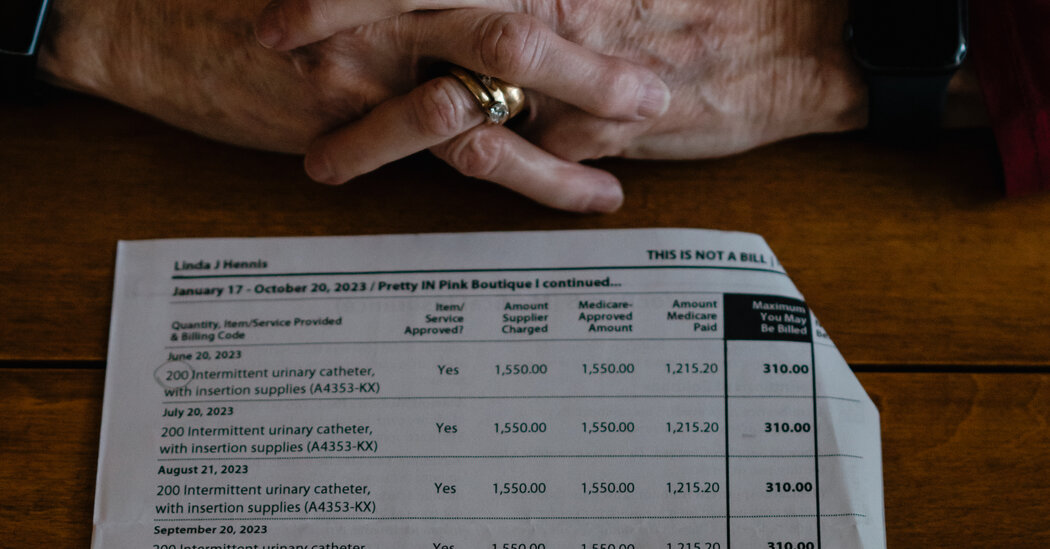

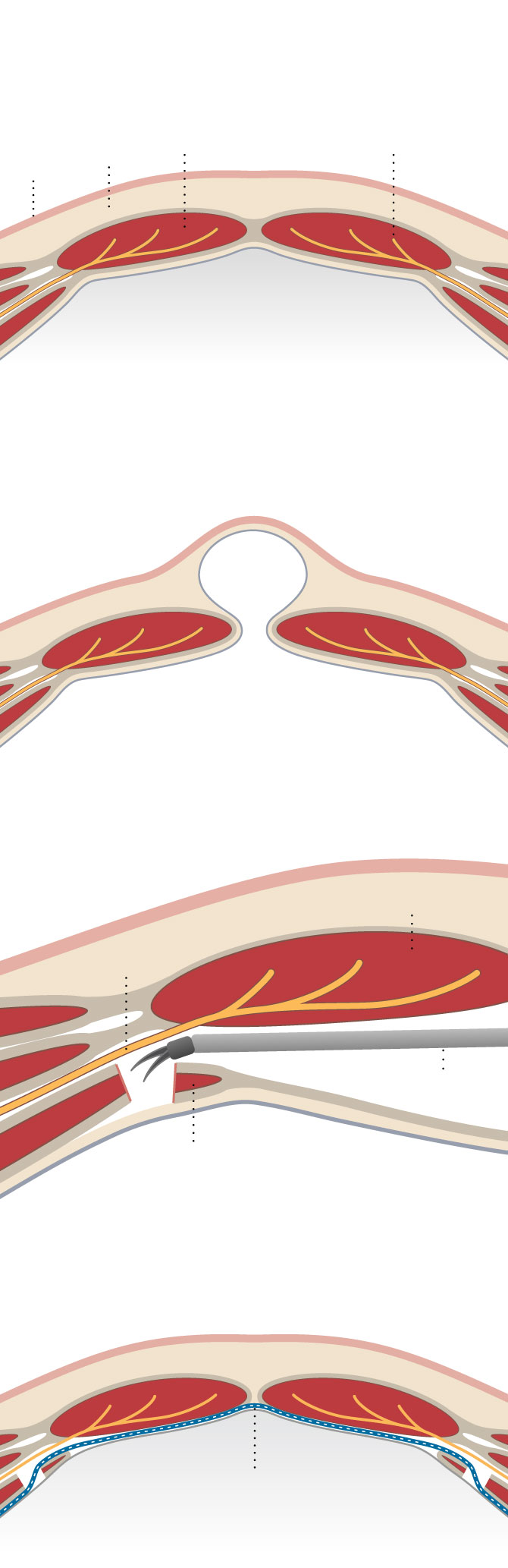

More surgeons are opting for a complicated hernia repair that they learned from videos on social media showing shoddy techniques.The bulge on the side of Peggy Hudson’s belly was the size of a cantaloupe. And it was growing.“I was afraid it would burst,” said Ms. Hudson, 74, a retired airport baggage screener in Ocala, Fla.The painful protrusion was the result of a surgery gone wrong, according to medical records from two doctors she later saw. Using a four-armed robot, a surgeon in 2021 had tried to repair a small hole in the wall of her abdomen, known as a hernia. Rather than closing the hole, the procedure left Ms. Hudson with what is called a “Mickey Mouse hernia,” in which intestines spill out on both sides of the torso like the cartoon character’s ears.One of the doctors she saw later, a leading hernia expert at the Cleveland Clinic, doubted that Ms. Hudson had even needed the surgery. The operation, known as a component separation, is recommended only for large or complex hernias that are tough to close. Ms. Hudson’s original tear, which was about two inches, could have been patched with stitches and mesh, the surgeon believed.Component separation is a technically difficult and risky procedure. Yet more and more surgeons have embraced it since 2006, when the approach — which had long been used in plastic surgery — was adapted for hernias. Over the next 15 years, the number of times that doctors billed Medicare for a hernia component separation increased more than tenfold, to around 8,000 per year. And that figure is a fraction of the actual number, researchers said, because most hernia patients are too young to be covered by Medicare.In skilled hands, component separations can successfully close large hernias and alleviate pain. But many surgeons, including some who taught themselves the operation by watching videos on social media, are endangering patients by trying these operations when they aren’t warranted, a New York Times investigation found.Dr. Michael Rosen, the Cleveland Clinic surgeon who later repaired Ms. Hudson’s hernias, helped develop and popularize the component separation technique, traveling the country to teach other doctors. He now counts that work among his biggest regrets because it encouraged surgeons to try the procedure when it wasn’t appropriate. Half of his operations these days, he said, are attempts to fix those doctors’ mistakes.“It’s unbelievable,” Dr. Rosen said. “I’m watching reasonably healthy people with a routine problem get a complicated procedure that turns it into a devastating problem.”Ms. Hudson’s original surgeon, Dr. Edwin Menor, said he learned to perform robotic component separation a few years ago. He said he initially found the procedure challenging and that some of his operations had been “not perfect.”Dr. Menor said that he now performs component separations a few times a week and that, with additional experience, “you improve eventually.” He said he had a roughly 95 percent success rate. In Ms. Hudson’s case, he said, the use of component separation was warranted based on the complexity of her hernia and her history of prior abdominal surgeries.Intuitive debuted the da Vinci robot in 2000, with the idea that more precise surgery would shorten recovery times. It comes with a built-in camera for doctors to create high-resolution videos of their surgeries.Marcin Bielecki/EPA, via ShutterstockComponent separation must be practiced dozens of times to master, experts said. But one out of four surgeons said they taught themselves how to perform the operation by watching Facebook and YouTube videos, according to a recent survey — part of a broader pattern of surgeons of all stripes learning new techniques on social media with minimal professional oversight.Other hernia surgeons, including Dr. Menor, learned component separation at events sponsored by medical device companies. Intuitive, for example, makes a $1.4 million robot known as the da Vinci that is sometimes used for component separations. Intuitive has paid for hundreds of hernia surgeons to attend short courses to learn how to use the machine for the procedure. The company makes money not only from selling the machines but also by charging some hospitals every time they use the robot.Many surgeons — even some paid by device companies to teach the technique — haven’t learned how to properly carry out component separation with the da Vinci, The Times found. In fact, at times they are teaching one another the wrong techniques.The robot comes with a built-in camera that makes it easy for doctors to record high-resolution videos of their surgeries. The videos are often shared online, including in a Facebook group of about 13,000 hernia surgeons. Some videos capture surgeons using shoddy practices and making appalling mistakes, surgeons said.One instructional video, paid for by another major medical device company, showed a surgeon slicing through the wrong part of the muscle with the da Vinci. Experts said the result could have been devastating, turning the abdominal muscles into what one described as “dead meat.”Peper Long, a spokeswoman for Intuitive, said the company hired “experienced surgeons” to lead its training courses. “The rise in robotic-assisted hernia procedures reflects the clinical benefits that the technology can offer,” she said.In interviews with The Times, more than a dozen hernia surgeons pointed to another reason for the surging use of component separations: They earn doctors and hospitals more money. Medicare pays at least $2,450 for a component separation, compared with $345 for a simpler hernia repair. Private insurers, which cover a significant portion of hernia surgeries, typically pay two or three times what Medicare does.Ms. Hudson with Dr. Michael Rosen, who fixed her hernia, at the Cleveland Clinic. “I’m watching reasonably healthy people with a routine problem get a complicated procedure that turns it into a devastating problem,” he said.Daniel Lozada for The New York TimesRepeat BillingsFixing the torn muscles of a hernia is like closing a suitcase: It’s usually not too difficult to bring the two sides together and zip it up. But a large hernia, like an overstuffed bag, doesn’t have enough slack to bring the muscles back together.Around 2006, surgeons adapted a technique from plastic surgery, called component separation, to close large hernias. On each side of the torso, they carefully cut the muscle to create slack, resulting in something like an extra zipper in expandable luggage.Component SeparationA surgical technique called a component separation can repair large or complex hernias.

Read more →