A new workshop explores the right of Indigenous people to govern the collection, ownership and use of their biological and cultural data.When Krystal Tsosie introduces her genomics students to the concept of biocommercialism — the extraction of biological resources from Indigenous communities without benefit — she always uses the same example: the Human Genome Diversity Project.The researchers who conceived of the project in the 1990s aimed to collect samples from human populations around the world, with particular emphasis on what they deemed “vanishing” Indigenous populations. “A lot of that information is now publicly available to advance the course of science,” said Ms. Tsosie, a genetics researcher at Vanderbilt University and a member of the Navajo Nation. “But who accesses these data sets?”Ms. Tsosie, answering her own question, cited as examples Ancestry and 23andMe, two companies that commercialize and profit from Indigenous genomic data sourced without consent from people in Central and South America. In 2018, 23andMe sold access to its database of digital sequence information to GlaxoSmithKline for $300 million. In 2020, 23andMe licensed a drug compound it developed from its trove of genetic information.Accordingly, Ms. Tsosie helped to organize IndigiData, a four-day remote workshop that took place for the first time in June. The workshop’s core goal was to introduce data science skills to undergraduates and graduates, and the definition of data was expansive, from the genetic sequences of soil microbiomes to traditional worldviews.“If you can’t view oral history as data, as something that can be parsed and archived and used to predict things, then you’re missing out on a whole data set,” said Keolu Fox, a Native Hawaiian geneticist at the University of California, San Diego, who presented at the workshop.Ms. Tsosie helped to organize IndigiData, a four-day remote workshop that took place for the first time in June. Tomás Karmelo Amaya for The New York TimesThe workshop centered on Indigenous data sovereignty, the idea that nations have the right to govern the collection, ownership and application of their own data. The movement pushes back on a long history of how researchers have taken Native data without permission, often stigmatizing the communities who participated or disregarding their customs surrounding the dead. In one infamous example, an Arizona State University researcher studying the high rates of diabetes in the Havasupai Tribe, who live near the Grand Canyon, gave other researchers access to the samples without the tribe’s consent. When the Havasupai learned of this, they went to court, won their samples back and banished the university from their borders.“Why are we over here spitting in tubes, giving our genomes away when we know that type of information can be used to make pharmaceutical drugs?” Dr. Fox asked. “Why not position ourselves so we’re in control of a treasure chest of data?”Organizing the ConferenceMs. Tsosie, one of the leaders of the conference, started her career in cancer biology. But she realized early on that any success she might have developing a cancer therapy drug might never reach her own community. Ms. Tsosie’s father worked for the Phoenix Indian Medical Center in Arizona for 42 years, and she remembered how difficult it was for her tribal community to access specialty services.“What am I doing in cancer biology?” Ms. Tsosie remembered thinking. She switched her academic focus and is now a graduate student in genomics and health disparities.In 2012, Ms. Tsosie met Joseph M. Yracheta, who is of the P’urhepecha and Raramuri peoples, through the Summer Internship for Indigenous Peoples in Genomics, a workshop that trains researchers in genetic science. They started talking about data ethics, and a few years later Matt Anderson, a microbiologist at Ohio State University and a descendant of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, joined the conversation. The organizers recognized that there were limited resources to train Indigenous people how to think about and interpret their data.In January, with funding from the Amgen Foundation and the National Science Foundation, the workshop began to take shape. The participants hail from Indigenous communities across the country and internationally, and have wide-ranging research interests, such as archaeology and pollinators. “What ties us together is colonialism,” Dr. Fox said, and laughed.The Environmental MicrobiomeThe theme of the inaugural conference was environmental microbiomes, which the organizers felt would resonate with participants. An individual’s microbiomes — the communities of microorganisms that live inside and on a person — is deeply intertwined with the surroundings; for instance, the composition of the gut microbiome can be altered by diet as well as air pollution.In recent years, the “vanishing” rhetoric of the Human Genome Diversity Project has shifted to refer to the “vanishing” microbiome of traditional communities, Dr. Anderson said. “Except instead of people, they’re talking about the microbes associated with people,” Dr. Anderson said. One 2018 article in the journal Science emphasized the need to collect samples from “traditional peoples in developing countries” in order “to capture and preserve the human microbiota while it still exists.”Ms. Tsosie started her career in cancer biology but is now a graduate student in genomics and health disparities.Tomás Karmelo Amaya for The New York TimesMr. Yracheta, who is the managing director of the Native BioData Consortium — the first biobank in the U.S. led by Indigenous scientists and tribal members — believes the microbiome will be one of the next targeted data sets that Western scientists may seek from Indigenous communities. In Tanzania, the Hadza people have been studied extensively for the “richness and biodiversity” of their gut microbiota.“Native DNA is so sought after that people are looking for proxy data, and one of the big proxy data is the microbiome” Mr. Yracheta said. “If you’re a Native person, you have to consider all these variables if you want to protect your people and your culture.”In a presentation at the conference, Joslynn Lee, a member of the Navajo, Laguna Pueblo and Acoma Pueblo Nations and a biochemist at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colo., spoke about her experience tracking the changes in microbial communities in rivers that experienced a mine wastewater spill in Silverton, Colo. Dr. Lee also offered practical tips on how to plan a microbiome analysis, from collecting a sample to processing it.In a data-science career panel, Rebecca Pollet, a biochemist and a member of the Cherokee Nation, noted how many mainstream pharmaceutical drugs were developed based on the traditional knowledge and plant medicine of Native people. The anti-malarial drug quinine, for example, was developed from the bark of a species of Cinchona trees, which the Quechua people historically used as medicine. Dr. Pollet, who studies the effects of pharmaceutical drugs and traditional food on the gut microbiome, asked: “How do we honor that traditional knowledge and make up for what’s been covered up?”One participant, the Lakota elder Les Ducheneaux, added that he believed that medicine derived from traditional knowledge wrongly removed the prayers and rituals that would traditionally accompany the treatment, rendering the medicine less effective. “You constantly have to weigh the scientific part of medicine with the cultural and spiritual part of what you’re doing,” he said.IndigiData in the FutureOver the course of the IndigiData conference, participants also discussed ways to take charge of their own data to serve their communities.Mason Grimshaw, a data scientist and a board member of Indigenous in A.I., talked about his research with language data on the International Wakashan A.I. Consortium. The consortium, led by an engineer, Michael Running Wolf, is developing an automatic speech recognition A.I. for Wakashan languages, a family of endangered languages spoken among several First Nations communities. The researchers believe automatic speech recognition models can preserve fluency in Wakashan languages and revitalize their use by future generations.Mason Grimshaw is a data scientist and a board member of Indigenous in A.I., in Rapid City, S.D.Dawnee LeBeau for The New York TimesTypical language models, such as Apple’s voice-controlled Siri, often try to predict the next word, or set of words, based on the start of a sentence or a prompt. But such models might falter under the cultural nuances of many Indigenous languages, Mr. Grimshaw noted. “The Wakashan folks have certain stories you would only tell in certain kinds of weather or at certain times of day,” he said, by way of example.Additionally, many Indigenous languages are polysynthetic; they do not have fixed vocabularies but rely instead on the recombinations of small building blocks of words. A polysynthetic language like Lakota technically allows there to be infinite words, Mr. Grimshaw said. Indigenous languages often have much less recorded language data to analyze, such as audio files of speakers in conversation, than more common languages do.Mr. Grimshaw sees these complications not as a problem but as a puzzle to be unscrambled. When asked about his wildest data dreams by a participant at the conference, Mr. Grimshaw smiled. “I want a Lakota version of Siri,” he said.IndigiData has funding for the next four years, and the organizers hope that the conference next year will be held in person at the Native BioData Consortium on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation. That location, Dr. Anderson noted, is a one-day drive from 13 tribal colleges.Dr. Fox hopes the conference will train the next generation of Indigenous data scientists not just to protect their data but to be empowered by its possibilities.“I’m not saying that I like capitalism,” he said. “But data is power, and that’s the way for us to revitalize our communities.”

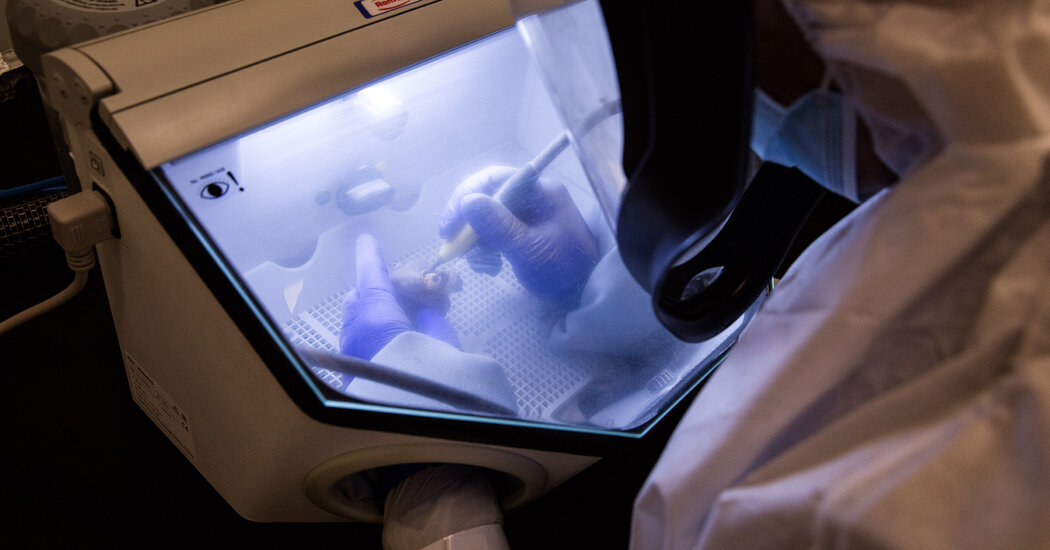

Read more →