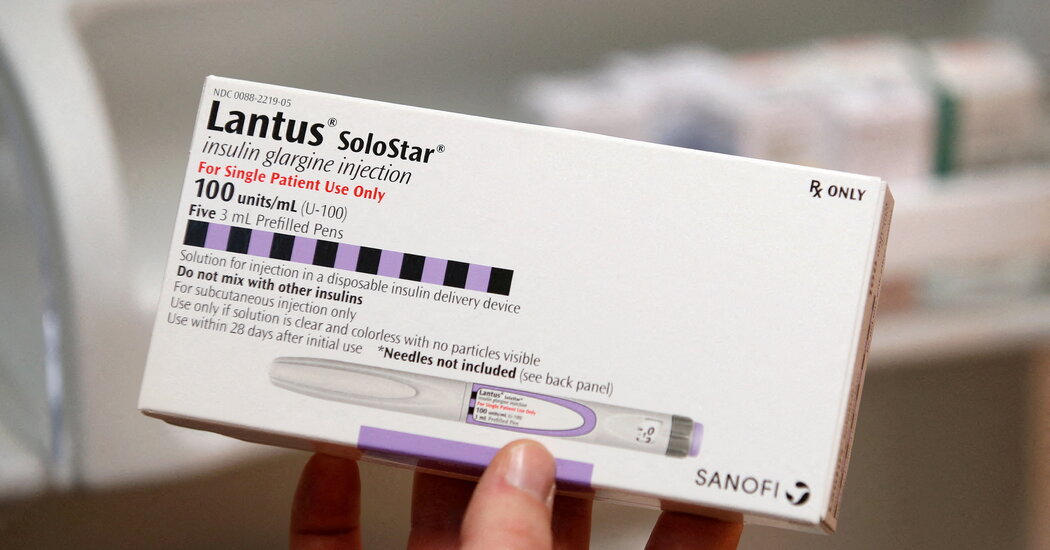

Many employers and government programs won’t cover costly obesity medications. A lawsuit is challenging one such policy.Jeannette Simonton was a textbook candidate for the obesity drug Wegovy when her doctor prescribed it to her in February.At 5 feet 2 inches and 228 pounds, she had a body mass index of nearly 42 — well above the cutoff U.S. regulators had approved for eligibility for the medication. She also had serious joint problems after decades of struggling with her weight.But her insurance refused to pay for the medication, citing a blanket ban on covering weight-loss drugs, according to a letter Ms. Simonton received in March from her benefits administrator.Now, Ms. Simonton is suing the Washington State agency that purchases health insurance for public employees like her. Her lawyers argue that the state’s health plans are discriminating against Ms. Simonton — and others who, like her, are seeking weight-loss drugs — in violation of state law, which recognizes obesity as a type of disability.Ms. Simonton’s case is a flashpoint in the conflict over whether health insurance should have to cover obesity drugs. The challenge for payers is that the medications would be hugely costly if they were broadly covered in the United States, where more than 100 million people are obese.The lawsuit is likely to be closely watched as a test of whether health plans can refuse to pay for obesity drugs. Ms. Simonton is being represented by a Seattle law firm, Sirianni Youtz Spoonemore Hamburger, that has a long track record of challenging health insurance restrictions, including those for costly hepatitis C cures.Wegovy and other appetite-suppressing drugs are in huge demand because they are stunningly effective in helping patients lose weight. But the scale of that demand would pose an unprecedented financial burden for the employers and government programs that shoulder most of the costs of prescription drugs. Wegovy, Novo Nordisk’s high-dose version of its popular drug Ozempic, has a sticker price of over $16,000 a year.More payers have recently begun covering the obesity medications, encouraged by research suggesting that the drugs may pay for themselves in the long run by improving patients’ health. But others say they simply cannot afford to cover the medications.Ms. Simonton, 57, a nurse who is well-versed on the health benefits of the drugs, said she saw the refusal to cover her Wegovy as shortsighted.“They’re being penny wise and pound foolish,” she said. “What will they be paying in 10, 15 years if I don’t continue to lose the weight?”The agency Ms. Simonton is suing, the Washington State Health Care Authority, declined to comment. Ms. Simonton gets her health insurance through the public hospital where she works. As part of her compensation, her hospital pays premiums to the state, which the Health Care Authority uses to pay for her health plan. The agency has authority over which drugs are covered.Wegovy is in a class of injectable drugs known as GLP-1s, named after the natural hormone whose effects they emulate. The drugs have been used for years to treat Type 2 diabetes but more recently have been recognized for their extraordinary power to slash body weight.Wegovy is in a class of injectable drugs that have been used for years to treat Type 2 diabetes but more recently have been recognized for their extraordinary power to slash body weight.Jim Vondruska/ReutersAbout 36 million people with Type 2 diabetes in the United States — as well as about 18 million who are obese but not diabetic — have access to GLP-1s through their health plans, according to analysts at the investment bank Jefferies. That is about 17 percent of the country’s insured people.Federal law prohibits Medicare from paying for drugs for weight loss, a ban that persists largely because of the staggering costs. If Congress were to overturn the ban, one projection from academic researchers estimates that two million Medicare beneficiaries — 10 percent of older people with obesity — would take Wegovy. Under that scenario, the government’s annual expenditure would be $27 billion, nearly a fifth of the yearly spending for Medicare’s Part D program covering prescription drugs taken at home.Employers and state health insurance programs for public employees face a similar dilemma. In Arkansas, where 40 percent of people on the plan for state employees have obesity, covering the drugs would cost $83 million annually. The Wisconsin program would have to come up with an additional $25 million annually.“Employers don’t suddenly have a new pot of money to pay for higher health insurance premiums,” said Dr. Steven Pearson, president of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which assesses the value of medicines. “We’re talking about big changes to companies’ ability to provide other benefits, wage increases, new hires, and they may also have to turn that into higher premiums for their own employees.”Another worry for employers is that they may not actually reap the savings of investing in weight-loss medications. Averted heart attacks and avoided hospital stays made possible by the drugs may not manifest in savings until years down the line, when a patient has left that employer.But advocates for patients with obesity see stigma and bias at play when health plans view weight-loss treatment as akin to unnecessary vanity procedures.Ms. Simonton, who lives in Ellensburg, Wash., has had obesity for as long as she can remember. At one point in her 40s, she weighed 424 pounds. After she underwent an operation to reduce the size of her stomach, her weight fluctuated for years above 250 pounds.The weight has taken a toll. With osteoarthritis so bad that the bones in her knees were rubbing against one another, she has already had her right knee replaced and has surgery for her left scheduled for next month. “I wondered if I was going to have a nursing career left,” she said.Last year, she started taking Mounjaro, another powerful GLP-1 medication, with most of her costs covered by the drug’s manufacturer, Eli Lilly. When that assistance ran out, she paused treatment while her doctors helped her seek insurance coverage for the Novo Nordisk drug.In February, frustrated by the lack of progress, Ms. Simonton began paying out of pocket to obtain a version of the Novo Nordisk medication from a compounding pharmacy.Since she started taking GLP-1 drugs in September 2022, she has lost 76 pounds. She now weighs 191 pounds.“My life has changed, in an amazing way,” she said. “It’s the first time where I’m not constantly thinking about food.”But to cover the out-of-pocket costs — nearly $2,000 so far — Ms. Simonton and her husband have reduced their spending on groceries and cut their retirement savings.Ms. Simonton’s lawsuit, filed in state court in Washington last month, is seeking to force her health plan to pay for Wegovy going forward, as well as reimbursement from when she was denied coverage. Her lawyers are seeking class-action status on behalf of others like her who are insured through plans for public and school workers in Washington State.In 2019, Washington State’s Supreme Court ruled that obesity is “always” a protected disability under the state’s anti-discrimination law. Other courts outside the state have ruled that obesity is not usually protected.

Read more →