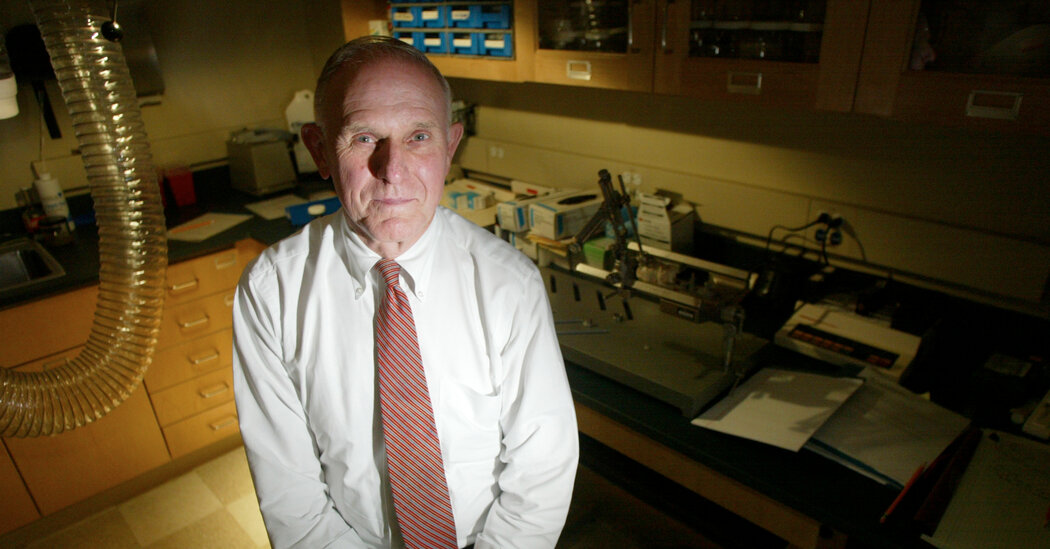

The drugs had been the third rail of scientific inquiry. But in a landmark study, he saw them as a legitimate way to help alleviate suffering and even to reach a mystical state.Roland Griffiths, a professor of behavioral science and psychiatry whose pioneering work in the study of psychedelics helped usher in a new era of research into those once banned substances — and reintroduced the mystical into scientific discourse about them — died on Monday at his home in Baltimore. He was 77.The cause was colon cancer, said Claudia Turnbull, a longtime friend.Dr. Griffiths, a distinguished psychopharmacologist and professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, spent decades studying the mechanisms of dependence on mood-altering drugs. He published scores of papers on opiates and cocaine, on sedatives and alcohol, on nicotine and caffeine.His work on caffeine, which he noted was the most commonly used drug in the world, was groundbreaking, showing that, yes, it was addictive, that withdrawal could be painful and that caffeine dependence was a “clinically meaningful disorder.”But in August 2006 he published a paper that wasn’t just groundbreaking; it was mind-blowing.The paper had an unusual title: “Psilocybin Can Occasion Mystical-Type Experiences Having Substantial and Sustained Personal Meaning and Spiritual Significance.” And when it appeared in the magazine Psychopharmacology, it caused a media ruckus.“The God Pill,” read the headline in The Economist. Here was the first double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study in decades to examine the psychological effects of a psychedelic on what scientists call “healthy normals” — healthy volunteers. Its focus was not on the beneficial properties of the drug for those suffering from depression, or being treated for cancer, or facing end-of-life terrors, or trying to quit smoking. Those landmark studies would come later.This work involved trained doctors administering high doses of psilocybin — the psychoactive, or mind-altering, component found in the psilocybe genus of mushrooms — to healthy people in a controlled, living room-like setting.Eighty percent of the participants described the experience as among the most revelatory and spiritually meaningful episodes of their lives, akin to the death of a parent or the birth of a child, as Dr. Griffiths often said.Their experience had all the attributes of a mystical event. They described profound feelings of joy, love and, yes, terror, along with a sense of interconnectedness and even an understanding of a sublime, sacred and ultimate reality.Such positive effects on their mood and behavior lasted for months and even years, as the author Michael Pollan discovered when he interviewed many of the participants for his 2018 book, “How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression and Transcendence.”“To listen to these people describe the changes in their lives inspired by their psilocybin journeys is to wonder if the Hopkins session room isn’t a kind of human transformation factor,” Mr. Pollan wrote.But Dr. Griffiths’s work showed that researchers could do more than induce a mystical experience in a lab; they could also use the tools of science — brain imaging, for example — to prospectively, as he put it, examine the nature of consciousness and of religious experience.As Charles Schuster, a former director of the government’s National Institute on Drug Abuse, told The New York Times in 2006, “This represents a landmark study, because it is applying modern techniques to an area of human experience that goes back as long as humankind has been here.”In a phone interview, Mr. Pollan said, “Roland had such a sterling reputation as being a rigorous and conscientious scientist.”“No one of his stature had stepped into this area in such a long time that it gave a lot of other people confidence,” he added. “When he presented this completely weird study, which was so out there for science, it could have been dumped on, but it wasn’t.”Dr. Griffiths’s work, which began in 1999, was endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration as well as a cohort of experts that included the former deputy of the drug czar under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. And it ushered in what many have called a renaissance in psychedelic research.“The fact that psychedelic research was being done at Hopkins — considered the premier medical center in the country — made it easier to get it approved here,” said Anthony P. Bossis, a psychologist specializing in palliative care at New York University.He told Mr. Pollan that Dr. Griffiths’s work had paved the way for him and his colleagues to begin using psilocybin to successfully treat anxiety in cancer patients.Theirs was not the only institution to do so. Similar research involving cancer patients, alcoholics, smokers and sufferers of depression began in earnest in this country and overseas following the publication of Dr. Griffiths’s paper.“It was an amazing study,” Dr. Bossis told Mr. Pollan, “with such an elegant design. And it opened up the field.”Dr. Griffiths spoke at an academic conference in Austin, Texas, in March 2022. He learned he had Stage 4 colon cancer earlier this year. Travis P Ball via Getty Images for SXSWPsychedelics had been the third rail of scientific inquiry ever since Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert were thrown out of Harvard for passing out LSD with messianic fervor in the early 1960s. By the end of that decade, psychedelics had been declared controlled substances deemed illegal for recreational and medical use.Yet beginning in the 1950s, well before Dr. Leary exhorted a generation to “turn on, tune in and drop out,” LSD — a synthetic chemical derived from a fungus, along with psilocybin and other psychedelics — were being studied and used successfully to treat alcoholism, depression, anxiety and distress among the terminally ill.The term psychedelic was coined in 1956 and drawn from the Greek root psyche, which translates to mind or soul. Freighted with the counterculture baggage of the 1960s, however, it devolved from its original meaning as a mind-altering drug into an aesthetic rendered in loopy typefaces and black-light posters.Dr. Griffiths was well-suited to bring psychedelics back as a legitimate area of scientific inquiry. Like many students of psychology of his generation, he had been heavily influenced by the work of B.F. Skinner, the “radical behaviorist” who disdained the focus on emotions and the unconscious that had long dominated the field and rather dwelled on the role of environment in determining, or conditioning, human behavior.In 1994, Dr. Griffiths began meditating regularly, which led to a transformative experience that, he said, “profoundly shifted my worldview and got me very curious about the nature of spiritual experiences.”He told Mr. Pollan that the experience was so profound that he nearly quit science to devote himself to a spiritual practice. But, as it happened, others were working to rehabilitate the study of psychedelics. One was Bob Jesse, a former vice president of the software company Oracle, who had established a nonprofit to encourage research on mystical experiences and whose introduction to Dr. Griffiths became the engine for what would soon change the direction of Dr. Griffiths’s research and reinvigorate the field.As researchers in his lab and elsewhere were studying the use of psilocybin in treating cancer patients, smokers and those with depression, he began focusing on examining the mystical aspects of their experiences and plumbing the nature of consciousness. He came to believe that the insights gleaned from psilocybin could have profound effects on humanity, which he saw heading toward disaster.Psychedelics, he suggested, might right the ship.“A hallmark feature of these experiences is that we’re all in this together,” he told The Chronicle of Higher Education in April. “It opens people up to this sense that we have a commonality and that we need to take care of each other.”Roland Redmond Griffiths was born on July 19, 1946, in Glen Cove, N.Y., to William and Sylvie (Redmonds) Griffiths. His father, who had trained as a psychologist, specialized in public health; his mother was a homemaker until the family moved to El Cerrito, Calif., in about 1951, after William had taken a job as a professor of public health at the University of California, Berkeley. There, Sylvie began successfully pursuing a master’s in psychology.Roland majored in psychology at Occidental College in Los Angeles and studied psychopharmacology at the University of Minnesota, earning his Ph.D. there in 1972. Johns Hopkins hired him immediately afterward, and he began concentrating his research on drug use and addiction.Dr. Griffiths is survived by his wife, Marla Weiner; his three children, Sylvie Grahan, Jennie Otis and Morgan Griffiths; five grandchildren; and his siblings, Kathy Farley and Mark Griffiths. His marriage in 1973 to Kristin Ann Johnson ended in divorce, as did his marriage to Diana Hansen.Dr. Griffiths was diagnosed with Stage 4 colon cancer earlier this year, a finding he came to embrace, as he told David Marchese of The New York Times Magazine. He established a foundation at Johns Hopkins to fund research on psychedelics. At his death, he was completing a paper about a study he had conducted in which clergy from a wide range of faiths received a high dose of psilocybin to see how it would affect their life and work.Notably, his laboratory’s first therapeutic study with psilocybin was with cancer patients, but Dr. Griffiths said he waited a bit before using a psychedelic to investigate his own condition. When he did — he took LSD — he approached the session like a reporter, and queried his cancer: What are you doing here? Is this going to kill me?“The answer was,” he told Mr. Marchese, “‘Yes, you will die, but everything is absolutely perfect; there’s meaning and purpose to this that goes beyond your understanding, but how you’re managing that is exactly how you should manage it.’”Long before his cancer diagnosis, Dr. Griffiths told Mr. Pollan that he hoped his own death would not be sudden, that he would have time to savor it. “Western materialism says the switch gets turned off and that’s it,” he said. “But there are so many other descriptions. It could be a beginning! Wouldn’t that be amazing.”Alain Delaquérière contributed research.

Read more →