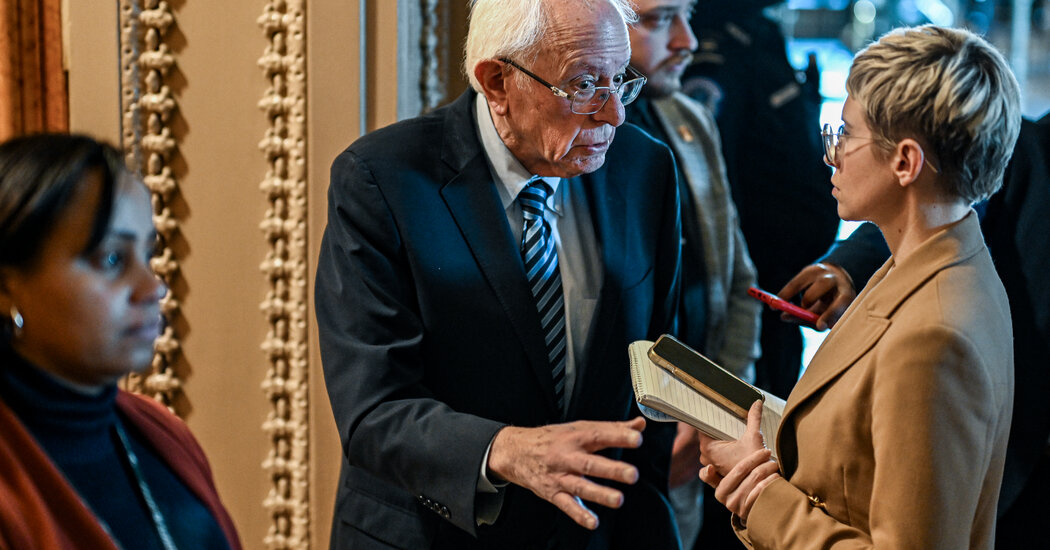

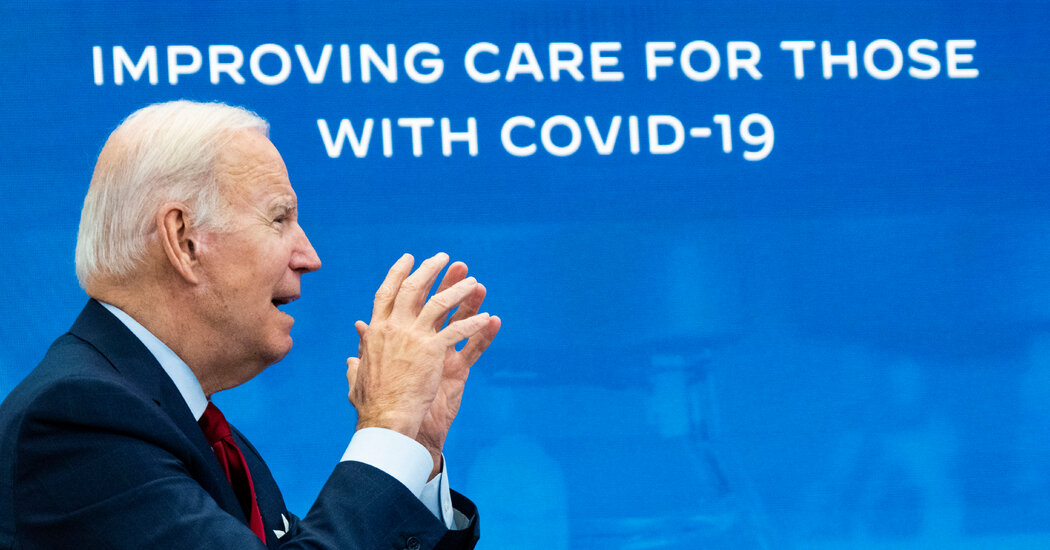

A top White House adviser said monoclonal antibody treatments, sometimes underused, could still be crucial in helping people with Covid-19 avoid getting very sick.WASHINGTON — Facing overcrowded hospitals and an unrelenting surge of Delta variant cases around the country, the Biden administration on Thursday renewed its call for health providers to use monoclonal antibody treatments, which can help Covid-19 patients who are at risk of getting very sick.Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, a White House adviser on racial equity in health, said at a news conference that federal “surge teams” deployed to hard-hit states were working to increase uptake of and confidence in the antibody drugs. They have already been administered to more than 600,000 people in the United States during the pandemic, she said, preventing hospitalizations and helping save lives. President Donald J. Trump received one such treatment when he was diagnosed with Covid-19 last year, before it had been authorized for emergency use.In states where vaccination has stalled and cases have soared, the treatments have become a key component of the federal strategy to reduce the toll of the worst outbreaks, underscoring how many Americans remain at risk.Distribution of doses, which are ordered by medical providers, increased fivefold from June to July. About 75 percent of the ordering is from regions of the country with low vaccination rates, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.The administration “continues to stand ready to assist states and territories and jurisdictions across the country to get more people connected” to the treatments, Dr. Nunez-Smith said on Thursday, though she emphasized that vaccination was still the best option for preventing Covid-19.Jeffrey D. Zients, the White House’s Covid-19 response coordinator, said the Biden administration has deployed more than 500 federal workers to help state health departments and hospitals combat the Delta variant, including emergency medical workers in Louisiana and Mississippi and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention teams in Tennessee, Illinois and Missouri.Dr. Nunez-Smith said the administration had conducted virtual trainings on how to administer the drugs for doctors and health system officials in Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming. In Arizona, federal teams are offering the treatments at two sites, where none of the Covid-19 patients who had received them had subsequently been hospitalized.The treatments, which the federal government pays for and makes free to patients, mimic antibodies that the immune system generates naturally to fight the coronavirus. They have been shown to sharply reduce hospitalizations and deaths when given to patients soon after symptoms appear, typically by intravenous infusion. There is also evidence that they may be able to prevent the disease entirely in certain people exposed to the virus. Unlike coronavirus vaccines, which take as long as six weeks to provide full protection, the antibody treatments can be given to patients who are already sick, with a more immediate effect.The latest data from the Department of Health and Human Services shows that just under half of the distributed supply of the treatments has been used, by more than 6,000 hospitals and other provider sites, dating back to late last year. The federal government relies on providers and state health departments to report their usage numbers and does not track the demographics of the patients who receive the drugs.Dr. Nunez-Smith said that shipments to Florida, which is experiencing a devastating surge in virus cases, had increased eightfold over the past month, and more than 108,000 courses of the treatments were shipped around the country in July.Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida on Thursday introduced a “rapid response unit” for administering the Regeneron treatment in Jacksonville, saying that the state would set up similar sites in other cities.Interest in the monoclonal antibodies has been spotty throughout the pandemic. When they were authorized last year, the treatments from Regeneron and Eli Lilly were expected to be in high demand and to serve as a bridge in fighting the pandemic before vaccinations ramped up. They were relentlessly promoted by Mr. Trump, who called the Regeneron treatment a “cure,” and top health officials in his administration.Still, they ended up sitting on refrigerator shelves in many places, even during recent surges. Many hospitals and clinics did not make the treatments a priority because of how time consuming and difficult to administer they were at the time, when they had to be given via intravenous infusion. Physicians can now administer the most frequently used treatment, from Regeneron, subcutaneously, or by injection..css-1xzcza9{list-style-type:disc;padding-inline-start:1em;}.css-3btd0c{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:1rem;line-height:1.375rem;color:#333;margin-bottom:0.78125rem;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-3btd0c{font-size:1.0625rem;line-height:1.5rem;margin-bottom:0.9375rem;}}.css-3btd0c strong{font-weight:600;}.css-3btd0c em{font-style:italic;}.css-w739ur{margin:0 auto 5px;font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.125rem;line-height:1.3125rem;color:#121212;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-family:nyt-cheltenham,georgia,’times new roman’,times,serif;font-weight:700;font-size:1.375rem;line-height:1.625rem;}@media (min-width:740px){#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-w739ur{font-size:1.6875rem;line-height:1.875rem;}}@media (min-width:740px){.css-w739ur{font-size:1.25rem;line-height:1.4375rem;}}.css-9s9ecg{margin-bottom:15px;}.css-16ed7iq{width:100%;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;justify-content:center;padding:10px 0;background-color:white;}.css-pmm6ed{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}.css-pmm6ed > :not(:first-child){margin-left:5px;}.css-5gimkt{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-size:0.8125rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-letter-spacing:0.03em;-moz-letter-spacing:0.03em;-ms-letter-spacing:0.03em;letter-spacing:0.03em;text-transform:uppercase;color:#333;}.css-5gimkt:after{content:’Collapse’;}.css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;-webkit-transform:rotate(180deg);-ms-transform:rotate(180deg);transform:rotate(180deg);}.css-eb027h{max-height:5000px;-webkit-transition:max-height 0.5s ease;transition:max-height 0.5s ease;}.css-6mllg9{-webkit-transition:all 0.5s ease;transition:all 0.5s ease;position:relative;opacity:0;}.css-6mllg9:before{content:”;background-image:linear-gradient(180deg,transparent,#ffffff);background-image:-webkit-linear-gradient(270deg,rgba(255,255,255,0),#ffffff);height:80px;width:100%;position:absolute;bottom:0px;pointer-events:none;}.css-uf1ume{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-box-pack:justify;-webkit-justify-content:space-between;-ms-flex-pack:justify;justify-content:space-between;}.css-wxi1cx{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:column;-ms-flex-direction:column;flex-direction:column;-webkit-align-self:flex-end;-ms-flex-item-align:end;align-self:flex-end;}.css-12vbvwq{background-color:white;border:1px solid #e2e2e2;width:calc(100% – 40px);max-width:600px;margin:1.5rem auto 1.9rem;padding:15px;box-sizing:border-box;}@media (min-width:740px){.css-12vbvwq{padding:20px;width:100%;}}.css-12vbvwq:focus{outline:1px solid #e2e2e2;}#NYT_BELOW_MAIN_CONTENT_REGION .css-12vbvwq{border:none;padding:10px 0 0;border-top:2px solid #121212;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-rdoyk0{-webkit-transform:rotate(0deg);-ms-transform:rotate(0deg);transform:rotate(0deg);}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-eb027h{max-height:300px;overflow:hidden;-webkit-transition:none;transition:none;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-5gimkt:after{content:’See more’;}.css-12vbvwq[data-truncated] .css-6mllg9{opacity:1;}.css-qjk116{margin:0 auto;overflow:hidden;}.css-qjk116 strong{font-weight:700;}.css-qjk116 em{font-style:italic;}.css-qjk116 a{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;text-underline-offset:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-thickness:1px;text-decoration-thickness:1px;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:visited{color:#326891;-webkit-text-decoration-color:#326891;text-decoration-color:#326891;}.css-qjk116 a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}“These are important tools,” said Dr. Dan Barouch, a virologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston who has worked with Regeneron on a study that showed that the company’s antibody treatment may be able to prevent Covid-19 when given to people living with someone infected with the coronavirus. “They have shown substantial therapeutic effects.”Dr. Rajesh Gandhi, an infectious disease physician at Massachusetts General Hospital who was an investigator for that study, said evidence of the benefit of the antibody treatments had only grown stronger in recent months. He said more needed to be done to educate physicians and patients on how effective they can be.“Patients need to know to call their physicians” and ask about the treatments, he said. “In 2020, people with mild Covid were told to stay home. That message needs to pivot to a more proactive message.”Regeneron has aired a series of television advertisements for its treatment this year.Virtually all Covid-19 patients receiving monoclonal antibodies during the Delta surge are getting the kind made by Regeneron, one of three that have been authorized by the Food and Drug Administration during the pandemic. The company estimated last week that its treatment was now reaching more than a quarter of eligible patients, up from less than 5 percent earlier in the pandemic.The F.D.A. last month expanded its emergency authorization of the Regeneron treatment so that it could be used to try to prevent Covid-19 in a small number of high-risk patients. They include people with certain health conditions who are not vaccinated or may not mount an adequate immune response, who have been exposed to the virus, or who live in nursing homes or prisons. It had previously been available, like the other monoclonal antibody treatments, only for high-risk patients who had already tested positive for the virus.The federal government in June indefinitely paused shipments of the first authorized monoclonal antibody treatment, from Eli Lilly, because new lab data suggested it would not work well in cases caused by the Beta and Gamma variants.The government has not ordered any doses of a third treatment, from GlaxoSmithKline and Vir, which is being used only minimally so far. Kathleen Quinn, a spokeswoman for GlaxoSmithKline, said the treatment was available at health care facilities in 26 states and U.S. territories.

Read more →