Sheldon Krimsky, Who Warned of Profit Motive in Science, Dies at 80

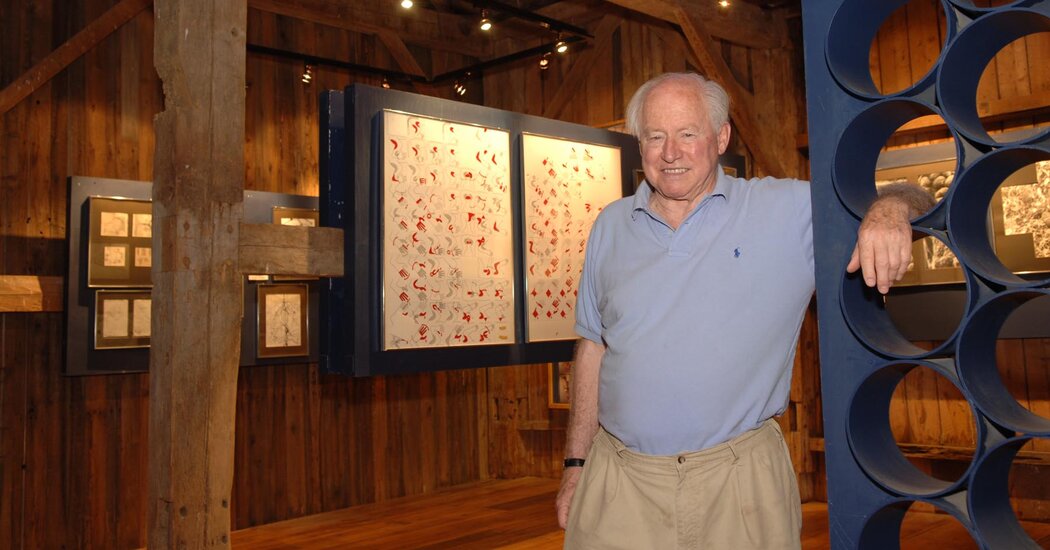

He delved into numerous scientific fields — stem-cell research, genetic modification of food and DNA privacy among them — and sought to pinpoint the dangers.Sheldon Krimsky, a leading scholar of environmental ethics who explored issues at the nexus of science, ethics and biotechnology, and who warned of the perils of private companies underwriting and influencing academic research, died on April 23 in Cambridge, Mass. He was 80. His family said that he was at a hospital for tests when he died, and that they did not know the cause.Dr. Krimsky, who taught at Tufts University in Massachusetts for 47 years, warned in a comprehensive way about the increasing conflicts of interest that universities faced as their academic researchers accepted millions of dollars in grants from corporate entities like pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.In his book “Science in the Private Interest” (2003), he argued that the lure of profits was potentially corrupting research and in the process undermining the integrity and independence of universities.But his wide-ranging public policy work went way beyond flagging the dangers inherent in the commercialization of science. The author, co-author or editor of 17 books and more than 200 journal articles, he delved into numerous scientific fields — stem-cell research, genetic modification of food and DNA privacy among them — and sought to pinpoint potential problems.“He was the Ralph Nader of bioethics,” Jonathan Garlick, a stem-cell researcher at Tufts and a friend of Dr. Krimsky, said in a phone interview, referring to the longtime consumer advocate.“He was saying, if we didn’t slow down and pay attention to important check points, once you let the genie out of the bottle there might be irreversible harm that could persist across many generations,” Dr. Garlick added. “He wanted to protect us from irreversible harm.”In “Genetic Justice” (2012), Dr. Krimsky wrote that DNA evidence is not always reliable, and that government agencies had created large DNA databases that posed a threat to civil liberties. In “The GMO Deception” (2014), which he edited with Jeremy Gruber, he criticized the agriculture and food industries for changing the genetic makeup of foods.His last book, published in 2021, was “Understanding DNA Ancestry,” in which he explained the complications of ancestry research and said that results from different genetic ancestry testing companies could vary in their conclusions. Most recently, he was starting to explore the emerging subject of stem-cell meat — meat made from animal cells that can be grown in a lab.Mr. Nader, in fact, had a long association with Dr. Krimsky and wrote the introduction to some of his books.“There was really no one like him: rigorous, courageous, and prolific,” Mr. Nader said in an email. “He tried to convey the importance of democratic processes in open scientific decision making in many areas. He criticized scientific dogmas, saying that science must always leave open options for revision.”In “Science in the Private Interest” (2003), Dr. Krimsky argued that the lure of profits had the potential to corrupt academic scientists’ research.Rowman & Littlefield PublishersSheldon Krimsky was born on June 26, 1941, in Brooklyn. His father, Alex, was a house painter. His mother, Rose (Skolnick) Krimsky, was a garment worker.Sheldon, known as Shelly, majored in physics and math at Brooklyn College and graduated in 1963. He earned a Master of Science degree in physics at Purdue University in 1965. At Boston University, he earned a Master of Arts degree in philosophy in 1968 and a doctorate in the philosophy of science in 1970.He met Carolyn Boriss, who was an artist and teacher and later became a playwright and author, in Cambridge in 1968. They married in 1970.She survives him, as do a daughter, Alyssa Krimsky Clossey; a son, Eliot; three grandchildren; and a brother, Sidney.Dr. Krimsky began his association with Tufts in what is now called the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning in 1974 and helped build it up over the decades. He also taught ethics at the Tufts University School of Medicine and was a visiting scholar at Columbia University, Brooklyn College, the New School and New York University.He began to explore the conflicts of interest in academic research in the late 1970s when he led a team of students on an investigation into whether the chemical company W.R. Grace had contaminated drinking wells in Acton, Mass.Dr. Krimsky has said that when the company learned that he would be releasing a negative report — the wells were later designated a Superfund site — one of its top executives asked the president of Tufts to bury the study and fire him. The president refused. But Dr. Krimsky was disturbed that the company had tried to interfere, and it prompted him to begin studying how corporations, whether or not they had made financial contributions, sought to manipulate science.“He spoke truth to power,” Dr. Garlick said. “He wanted to give voice to skepticism and give voice to the skeptics.”Dr. Krinsky was a longtime proponent of what he called “organized skepticism.”“When claims are made, you have to start with skepticism until the evidence is so strong that your skepticism disappears,” he told The Boston Globe in 2014. “You don’t in science start by saying, ‘Yes, I like this hypothesis and it must be true.’”He was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and headed its committee on scientific freedom and responsibility from 1988 to 1992. He was also a fellow of the Hastings Center on Bioethics and served on the editorial boards of seven scientific journals.When he wasn’t working, he liked to play the guitar and harmonica. He divided his time between Cambridge and New York City.“Shelly never gave up hope of a better world,” Julian Agyeman, a professor in Dr. Krimsky’s department and its interim chairman, was quoted as saying in a Tufts obituary. “He was the consummate activist-advocate-scholar.”

Read more →