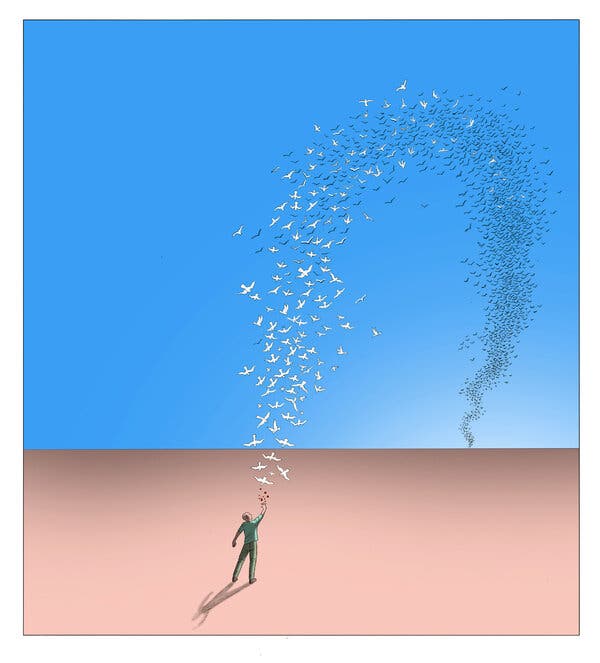

In England and America, selling bird seed for feeders is a big business. In Delhi, people toss bits of meat into the air for black kites. Fleets of ships ply the oceans to catch fish for domestic cats, the descendants of predatory land animals.Humans feed animals all the time, whether it’s our pets, the chickens we plan to eat or the ducks at the park pond, even though we shouldn’t.Throughout history in fat years and lean across many cultures, sometimes with no apparent reason, humans have fed animals of every imaginable stripe in every imaginable way. Some researchers think the desire to give food to other animals may drive domestication as much as the human desire to eat them does.Our Stone Age leftovers from the hunt may have fostered the domestication of dogs. Some of us give our beloved dead to vultures, which is a problem when the birds disappear. We fed and feed cats both tame and feral, sharks, alligators, deer, hedgehogs, bears, pigeons of all sorts, ducks, swans, zoo animals, lab animals, pets, farm animals and more.Now, a group of researchers in Britain is asking: Where does this desire to give food to other animals come from, and what has it meant for animals, humans and their shared environments?One striking possible answer is extinction. Domestication may be the death knell for wild progenitors. The ancestors of horses and cattle are gone. And while there are still wolves around, they are not thriving the way dogs are.Some feeding of animals is purely practical. You feed chickens today if you want to eat their eggs, or their wings, tomorrow. You can’t ride a starving horse. Animals used for experiments in laboratories have to be kept alive to get cancer.But a lot of feeding is unrelated to any return on investment. The black kites of Delhi reach population densities that may be the highest for raptors anywhere because of accidental and purposeful feeding. They rely on garbage and on the tasty and nutritious pests that garbage attracts. And they also benefit from the charity of Muslims who follow a tradition of tossing bits of meat into the air for the birds.Many Indians feed street dogs as a matter of course, treating them as animal neighbors. In a small city near Ahmedabad where I reported on anti-rabies efforts, residents told me that you can’t just give dogs plain leftover bread. You have to put some clarified butter on it, to make it palatable. The residents were middle class, and had both bread and butter to give, but I also met people who lived by the side of the road, with nothing more than mattresses and a few pots, who shared their food with dogs.Almost nothing about humans feeding animals is fully understood, largely because scholars have not given the subject a great deal of attention. And that, most of all, is what the researchers in England and Scotland want to change. With a four-year grant of more than $2 million from the Wellcome Trust, five researchers are pursuing a collaborative multidisciplinary attempt to give animal feeding its due, and begin to answer some puzzling questions. They call their project, “From ‘Feed the Birds’ to ‘Do Not Feed the Animals.’”Naomi Sykes, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, is the moving force behind the project.The first chickensChickens were one of the animals that led Dr. Sykes to this point of view, she said. She was working on some ancient sites in Britain and was surprised by what isotope studies of fossilized chicken bones suggested about the birds’ diet. Isotopes are different forms of elements like carbon and nitrogen, and researchers use the amount of one versus another to determine what animals or humans ate. Different grains or even grains from different geographical regions give different results, or values.“At sites where there’s a lot of chicken sacrifice to the gods of Mercury and Mithras” during the Roman occupation of Britain, Dr. Sykes said, “some of the values of those chickens just looked really bizarre.” It seemed the chickens were eating some sort of special diet. She talked to colleagues who told her that, in fact, chickens in Roman times that were to be sacrificed were sometimes fed a special diet of millet in preparation for their ritual slaughter.Eventually, chickens became a major food source. But they are one example, Dr. Sykes said, of a process of domestication in which feeding animals was more important at first than eating them.In addition to their religion, the Romans brought with them dogs and cats. Remains of the cats are found in settlements along with remains of wildcats that seemed to be living with or near humans as well, not as pets, but not quite wild either.“That got me thinking about cat diet, which then made me think, wait a minute, why do we feed domestic cats fish?” Dr. Sykes asked.Cats and ChristianityCould Christianity have something to do with it?“I think that monks start keeping cats for the first time, at least in Britain, as domestic pets,” she explained. “And they keep them because they want to have cats to eat the mice that eat the documents that they’re writing. And of course, monks are eating fish because they’re required to fast all the time.”Perhaps, she said, the monks fed the cats fish. The practice spread. And now an entire separate fishery catches fish for cat food.That worries Dr. Sykes because of its environmental impact. She says shoppers don’t put the same pressure for sustainability on the cat food fleets that they do on fisheries providing food for people.She began to wonder more generally: “What is it that encourages people to feed animals in the first place? What are the drivers of this throughout time and across cultures?”The four colleagues who joined Dr. Sykes in this project are: Angela Cassidy, also at the University of Exeter, who researches government policy on animals and has written about the internecine wars over the culling of badgers in Britain; Gary Marvin, an anthropologist at the University of Roehampton, who holds one of the world’s few professorships in human-animal studies; Stuart Black, a geochemist at the University of Reading; and Andrew Kitchener, principal curator of vertebrates at National Museums Scotland.The group is limiting its research geographically to Britain, for practical and logistical reasons. Its attention is mainly focused on the roles played by birds and cats in human life, as pets, pests, wild animals and zoo animals. In each case, they are asking the same broad questions about the origin of and reason behind various feeding methods, and what needs to change, if anything.For instance, Dr. Sykes will be looking at the archaeological records of cats from Roman settlements. Dr. Black will be studying the isotopes in modern and ancient cat bones to determine what cats were eating. Did monks’ cats in fact eat a lot of fish? He has already proved his technique on modern cats. “We can tell a fishy cat from a meaty cat,” he said. “In fact we can tell an Iams cat from a Whiskers cat,” although he concedes that knowledge may not be so useful in studying felines from the Middle Ages.Guy BilloutDr. Kitchener can look at old cat skeletons from Roman times and see that wildcats, now restricted to a small population in Scotland, were living in human settlements. Dr. Cassidy may look at political policies on feeding stray cats.Dr. Marvin said he would be working with postdoctoral researchers employed through the grant to look at cultural artifacts and historical literature to gauge how human attitudes toward cats have changed. He is also working with another postdoctoral researcher in Italy who will pursue anthropological studies among women who feed the feral cats of the coliseum in Rome. This interdisciplinary approach is very important, Dr. Marvin said. “To be in a room where a geneticist can be talking to an anthropologist and actually helping to answer questions, or ask more interesting questions — I think it’s quite a feat.”The feeding of birds suggests numerous avenues of research such as where, when, how and why it began. Also how is it that people come to view some birds as beloved but disdain others?And that in turn brings up the deep philosophical question of squirrels. In Britain, Dr. Marvin said, people spend somewhere around 200 million pounds feeding birds, presumably because they like them, and want to be close to nature. But they don’t like pigeons. And squirrels are beyond the pale. “You’ve got good and bad creatures in your back garden,” he said.Dr. Black’s isotope work is key to the interdisciplinary approach of this research, which is unusual, he said, because, “it’s a humanities-driven project.” The archaeologists, anthropologists and sociologists pose questions that he can help answer.For example, in the 1500s in England, laws known as the vermin acts set bounties for killing many animals, not just rats and mice. “There were things like crows, red kites, lots of birds of prey,” Dr. Black said. What caused the change in perspective? What were people thinking? Searching texts and literature from the time may bring some answers. But one idea is that the cold temperatures of the time, known as the little ice age, made food scarce and caused animals that normally might have been foraging in the wild to turn to human settlements to steal food or prowl for refuse.Studying old bone samples and comparing them to modern bones will show, for instance, if birds of prey in the 1500s depended more on human food than on traditional forage. Old, excavated raptor bones are plentiful to examine because 16th-century British citizens empowered by the vermin acts would kill the birds and toss them on garbage heaps.Chimp tea partiesIn addition, the project is taking one look at zoo inhabitants that is not simply a question of what tigers or koalas should eat. For years a British brand of tea, PG Tips, promoted its product with television advertisements that featured dressed up chimps having tea, with crumpets and scones, of course.The chimps lived at the Twycross Zoo, although chimp tea parties were common at zoos all over England. The zoo was founded in the 1960s by “two women who were mad about primates,” Lisa Gillespie, the zoo’s research and conservation manager said in an interview. “The ladies, as they were called,” she said, had trained the chimps for parties at the zoo and for advertisements, prompting the tea company to approach them. Income from those commercials greatly helped the zoo in its early days.“The animals ate human food, tea with milk in it, cake,” Ms. Gillespie said. Because adult chimps are too aggressive to keep as pets or use in advertisements, the zoo featured babies under 3 years old. Primatologists, zookeepers and the Twycross founders later acknowledged the harm in using the chimps that way, both from high sugar foods and from interfering with their natural behavioral development as chimpanzees. They were retired to the Twycross Zoo. With no tea or parties or costumes. The last of the PG Tips chimps to die was a female named Choppers in 2016.The chimps are, however, now unwittingly helping science. The National Museum of Scotland, where Dr. Kitchener works, collected the full skeletons of the PG Tips chimps to add to their trove of animal remains from other zoos and the wild.In studying the skeletons of Choppers and the other tea party chimps, Dr. Kitchener and other researchers identified signs of illness, probably related to what they were fed.Dr. Black is using isotope analysis to nail down the nutritional profile of the tea party chimps. The project is partnering with the Powell-Cotton Museum in Kent, which has a large collection of remains of wild chimps.He and Dr. Sykes have also been looking at changes in wildcats in Britain and their diet over time, and studying the bones of wild squirrels that were fed peanuts to help keep the population going. In adapting to the diet, the squirrels may not have developed the same jaw muscles as squirrels that have to struggle with pine cones, he said. Adaptations to changing diets for animals that live around or near humans can result in significant skeletal changes, he said, which raises questions about some physical changes that are thought to accompany domestication in different animals. Animals might have adapted to living around humans long before they became what we think of as domesticated. “So did the change come before they were domesticated or did the change come because they were domesticated?” he asked.The group will largely restrict itself to the last 2,000 years, but Dr. Black said some detours are irresistible, like the Tomb of the Eagles, a 5,000-year-old stone-age site in the Orkney Islands known officially as the Ibister Chambered Cairn. The cairn, or tomb, held about 16,000 human bones, and the remains of about 30 white-tailed sea eagles, Dr. Black said. “They were deposited over quite a significant period of time,” he said, “so it was people coming back, putting eagle remains in there.”He said: “The key question that nobody has really answered at the moment is whether people went out and killed and then deposited them as a sort of an offering. There is a suggestion that they may have been pets.” If that were the case, the eagles would have probably been eating a different diet than wild eagles that were foraging at sea.Dr. Sykes sees much of the human habit of feeding animals in the light of domestication, which she says happened as much through the process of humans feeding animals as it did through catching and corralling them to eat. That seems clear enough with our close companions, dogs and cats.It also seems that some animals that we now eat, like chickens and rabbits, may have first come into our lives not as food, but as eaters.And, she said, “domestication is not this thing that happened way back when, in this kind of neolithic moment where everybody got together and goes, we’re going to domesticate animals. I just don’t buy it. I think it’s something that has not only continued throughout time, but it’s really accelerating.”Bird feeding is just one example, and that sets off warning bells for her, because domestication and extinction often go together even if the cause and effect isn’t clear.The aurochs gave way to cattle. There are plenty of domestic cats in Britain, but just a few Scottish wildcats. Wolves are still here but not the wolves that dogs descended from. They are extinct. And modern wolves are just hanging on, while dogs might number a billion. Their future, at least in terms of numbers, is bright. As long as there are people, there will be dogs. No one knows what they will look like, and whether we will have to brush their teeth day and night, and spend a fortune on their haircuts. But they will be here.The same cannot be said of wolves. And as wild creatures go extinct, we all lose.

Read more →