A New Procedure Could Expand Reproductive Choices for Transgender Women

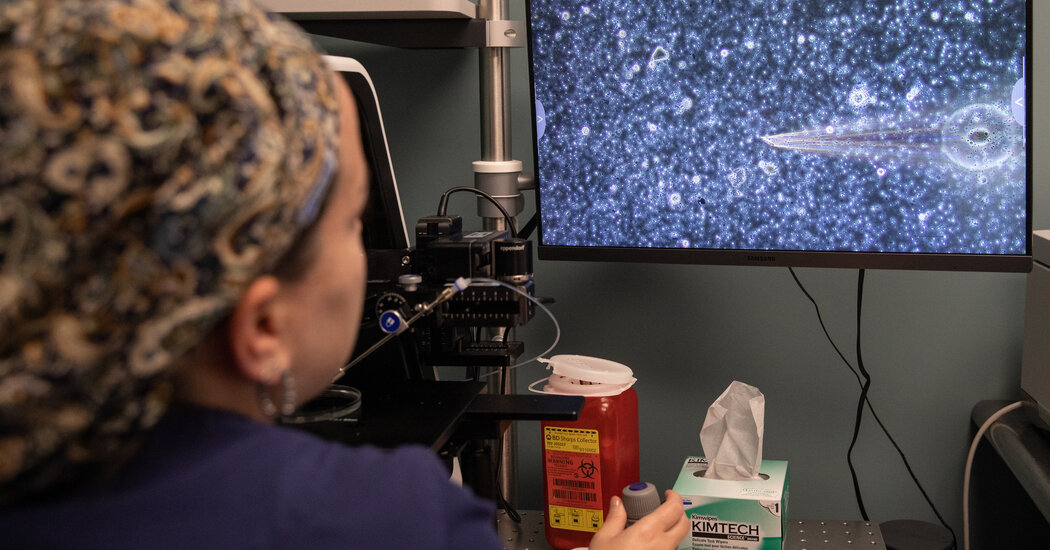

Retrieving viable sperm from men with low fertility and from people who have used estrogen therapy for years has been a challenge, doctors say. A new, less invasive technique has promise.Claire always knew that she wanted to start a family. But as a transgender woman who just turned 41, she also knew it could be complicated.Claire and her partner discussed having a baby together and, if possible, they wanted to use her sperm and her partner’s egg. But Claire, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect her family’s privacy, had been on estrogen therapy for 18 years, and the chances that doctors would find any viable sperm were slim.At the same time, Claire was scheduled to have her gender confirmation surgery, a vaginoplasty. The procedure would remove her penis and testicles and create a functional vagina, permanently ending her body’s sperm production.Transgender women take medications to suppress testosterone production and increase estrogen, which tend to decrease sperm production and often shut it down entirely. But a new procedure called extended sperm search and microfreeze, or E.S.S.M., makes retrieving that sperm possible, unless sperm production has stopped altogether.Using E.S.S.M., Dr. Michael Werner, a urologist specializing in sexual and reproductive health, was able to find and freeze more than 200 of Claire’s viable sperm. Her procedure was the first known time that doctors had been able to retrieve viable sperm in a transgender woman after more than two years of hormone treatments.Dr. Arie Berkovitz, an obstetrician and gynecologist and a male fertility expert at Assuta Hospital in Rishon LeZion, Israel, created the E.S.S.M. technique in 2017 as a treatment for men with low sperm counts.Sperm production requires consistent testosterone production in the testicles — 40 million total per ejaculate is considered normal. E.S.S.M. does not increase sperm production. With E.S.S.M., doctors are able to find and freeze small amounts of sperm from the ejaculate without side effects; finding such samples can otherwise be difficult in people who have undergone extended hormone therapy. Previously, patients with low sperm counts or those thoughts to have no sperm at all had to undergo an invasive surgery in which sperm was removed through a needle inserted into the testicle. The process can be painful and can damage the testes.“I was doing it for peace of mind so that I could be confident that I had tried everything,” Claire said of the procedure. “When I received the call that not only were there sperm but that there were so many, it was both astonishing and overwhelming.”In E.S.S.M., the semen sample is divided into tiny droplets and scanned using a high-powered microscope for several hours. Any sperm that are found are individually placed in a specialized device called a SpermVD and cryopreserved. Over 90 percent of them survive the freeze-and-thaw process.Dr. Michael Werner, a urologist specializing in sexual and reproductive health, at Maze Health in Manhattan.Jackie Molloy for The New York TimesDr. Joshua Safer, executive director for the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at the Mount Sinai Health System, said the surgery’s success was promising for transgender women who would like to start a family later in life.On Being Transgender in America‘Top Surgery’: Small studies suggest that breast removal surgery improves transgender teenagers’ well-being, but data is sparse. Some state leaders oppose such procedures for minors.In Montana: Transgender people born in the state will no longer be able to change the sex listed on their birth certificate under a new rule that is among the most restrictive in the country.Generational Shift: The number of young people who identify as transgender in the United States has nearly doubled in recent years, according to a new report.The Battle Over Gender Therapy: More teenagers than ever are seeking transitions, but the medical community is deeply divided about why — and what to do to help them.“My reaction is twofold: I’m surprised and impressed,” he said. Referring to the surgery, he added: “As an endocrinologist, we don’t know what the limits are.”Before her procedure, Claire went to a fertility clinic in Boston, at her doctor’s suggestion, to see if the bank could retrieve and store her sperm before her surgery. The clinic could not find any gametes, or sperm, in her ejaculate, even though she had stopped taking her hormones 10 months earlier.Her urologist in New York referred her to Maze Men’s Sexual Health, a fertility clinic and sperm bank led by Dr. Werner. By then, her vaginoplasty was just one day away, and rescheduling could take a long time, given the waiting list. E.S.S.M seemed like a long shot, so she was surprised at the result..css-1v2n82w{max-width:600px;width:calc(100% – 40px);margin-top:20px;margin-bottom:25px;height:auto;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-family:nyt-franklin;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1v2n82w{margin-left:20px;margin-right:20px;}}@media only screen and (min-width:1024px){.css-1v2n82w{width:600px;}}.css-161d8zr{width:40px;margin-bottom:18px;text-align:left;margin-left:0;color:var(–color-content-primary,#121212);border:1px solid var(–color-content-primary,#121212);}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-161d8zr{width:30px;margin-bottom:15px;}}.css-tjtq43{line-height:25px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-tjtq43{line-height:24px;}}.css-x1k33h{font-family:nyt-cheltenham;font-size:19px;font-weight:700;line-height:25px;}.css-1hvpcve{font-size:17px;font-weight:300;line-height:25px;}.css-1hvpcve em{font-style:italic;}.css-1hvpcve strong{font-weight:bold;}.css-1hvpcve a{font-weight:500;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);}.css-1c013uz{margin-top:18px;margin-bottom:22px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1c013uz{font-size:14px;margin-top:15px;margin-bottom:20px;}}.css-1c013uz a{color:var(–color-signal-editorial,#326891);-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;font-weight:500;font-size:16px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1c013uz a{font-size:13px;}}.css-1c013uz a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}What we consider before using anonymous sources. Do the sources know the information? What’s their motivation for telling us? Have they proved reliable in the past? Can we corroborate the information? Even with these questions satisfied, The Times uses anonymous sources as a last resort. The reporter and at least one editor know the identity of the source.Learn more about our process.Dr. Eric K. Seaman, a urologist who specializes in male reproductive health in Millburn, N.J., said that Claire’s success was uncommon.“It’s a Hail Mary that they were able to find any sperm after 18 years of hormonal therapy,” he said.Claire, who lives in Massachusetts, is one of about 1.6 million people in the United States who identify as transgender. For transgender women who want to undergo genital surgery, E.S.S.M. may be an option to preserve sperm.Dr. Safer, who is also the former president of the United States Professional Association for Transgender Health, said he believed this technology could benefit many of his patients. Since starting the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery in 2016, he has seen a surge in transgender people seeking hormone therapy and surgery. The center performs 800 to 900 gender-affirming surgeries each year, he said.“More and more people are feeling safer about identifying themselves as transgender and getting hormones and having medical interventions,” he said. “But in the gender-affirming care world, our clinics need to do a better job of getting kids to do fertility preservation before they’re getting on hormones.”But Dr. Seaman said he was concerned that there could be an increase in the miscarriage rate related to the use of E.S.S.M. The sperm that is recovered using the technique tends to be more fragile because of the extra time it takes to travel through the epididymis, part of the duct systems of the male reproductive organs, compared with surgical retrieval from the testicles, where the sperm and its DNA are more robust.Cryo-tanks are used for long-term storage of sperm samples at Maze Health. Jackie Molloy for The New York TimesThe treatment — and its potential drawbacks — do not apply only to transgender women. About 1 percent to 2 percent of men who are infertile, Dr. Seaman added, have severe male factor infertility, a condition in which no sperm is found in the semen; half of all infertile couples have male factor infertility, too. While there may be a higher chance of miscarriage for couples using sperm retrieved using E.S.S.M., the procedure is much less invasive than — and preferable to — having sperm surgically retrieved from the testes, Dr. Berkovitz said.“It’s an operation, and there are no invasive procedures without complications,” he said about surgical retrieval of sperm from the testes.Men with severe male factor infertility are already at a higher risk of causing pregnancies that result in miscarriage, he added, because sperm may be damaged as a result of the condition.As long as transgender women have normal sperm production, E.S.S.M. should not interfere with their producing a healthy baby, Dr. Berkovitz said.“In this case, she didn’t have low sperm count,” he said. “Genetically, her sperm was normal,” so her fertility would be preserved for future use.Doctors were able to freeze enough of Claire’s sperm for her to have 30 cycles of in vitro fertilization in the future.“It’s a second chance for transgender patients,” he said. “We can offer them fertility preservation without any pain or discomfort, and without an invasive procedure or operation.”Still, Dr. Werner encourages transgender young people to bank their sperm before any medical intervention to avoid the potential risks of fertility loss and leave their options open for the future.“Unfortunately, the vast majority of trans women who are transitioning aren’t given the option to bank their sperm, and once they’re put on hormones and have their testes surgically removed, their options have closed,” he said.He is now starting to see more transgender women coming to the clinic to bank their sperm.Claire said she also wished she had sought guidance sooner.“I’d encourage young people to bank their sperm,” she said. “I know I wish I’d done it earlier.”

Read more →