Can Virtual Reality Help Autistic Children Navigate the Real World?

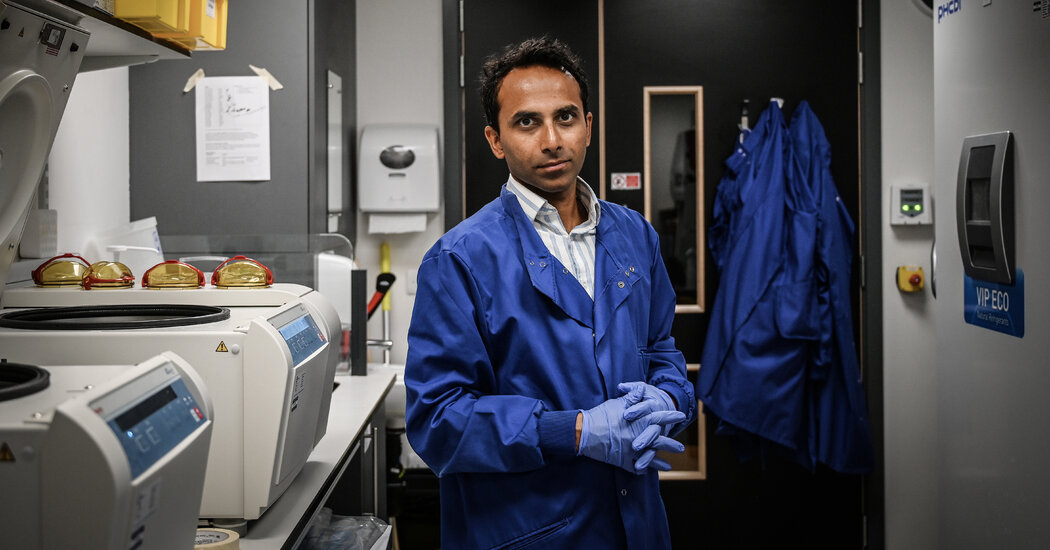

One company, Floreo, is hoping their tools will lead the way, despite some criticisms from autism self-advocates.This article is part of Upstart, a series on young companies harnessing new science and technology.Vijay Ravindran has always been fascinated with technology. At Amazon, he oversaw the team that built and started Amazon Prime. Later, he joined the Washington Post as chief digital officer, where he advised Donald E. Graham on the sale of the newspaper to his former boss, Jeff Bezos, in 2013.By late 2015, Mr. Ravindran was winding down his time at the renamed Graham Holdings Company. But his primary focus was his son, who was then 6 years old and undergoing therapy for autism.“Then an amazing thing happened,” Mr. Ravindran said.Mr. Ravindran was noodling around with a virtual reality headset when his son asked to try it out. After spending 30 minutes using the headset in Google Street View, the child went to his playroom and started acting out what he had done in virtual reality.“It was one of the first times I’d seen him do pretend play like that,” Mr. Ravindran said. “It ended up being a light bulb moment.”Like many autistic children, Mr. Ravindran’s son struggled with pretend play and other social skills. His son’s ability to translate his virtual reality experience to the real world sparked an idea. A year later, Mr. Ravindran started a company called Floreo, which is developing virtual reality lessons designed to help behavioral therapists, speech therapists, special educators and parents who work with autistic children.Mr. Ravindran adjusts his son’s VR headset between lessons. “It was one of the first times I’d seen him do pretend play like that,” Mr. Ravindran said of the time when his son used Google Street View through a headset, then went into his playroom and acted out what he had experienced in VR. “It ended up being a light bulb moment.”Valerie Plesch for The New York TimesThe idea of using virtual reality to help autistic people has been around for some time, but Mr. Ravindran said the widespread availability of commercial virtual reality headsets since 2015 had enabled research and commercial deployment at much larger scale. Floreo has developed almost 200 virtual reality lessons that are designed to help children build social skills and train for real world experiences like crossing the street or choosing where to sit in the school cafeteria.Last year, as the pandemic exploded demand for telehealth and remote learning services, the company delivered 17,000 lessons to customers in the United States. Experts in autism believe the company’s flexible platform could go global in the near future.That’s because the demand for behavioral and speech therapy as well as other forms of intervention to address autism is so vast. Getting a diagnosis for autism can take months — crucial time in a child’s development when therapeutic intervention can be vital. And such therapy can be costly and require enormous investments of time and resources by parents.The Floreo system requires an iPhone (version 7 or later) and a V.R. headset (a low-end model costs as little as $15 to $30), as well as an iPad, which can be used by a parent, teacher or coach in-person or remotely. The cost of the program is roughly $50 per month. (Floreo is currently working to enable insurance reimbursement, and has received Medicaid approval in four states.)A child dons the headset and navigates the virtual reality lesson, while the coach — who can be a parent, teacher, therapist, counselor or personal aide — monitors and interacts with the child through the iPad.The lessons cover a wide range of situations, such as visiting the aquarium or going to the grocery store. Many of the lessons involve teaching autistic children, who may struggle to interpret nonverbal cues, to interpret body language.Mr. Ravindran’s son raises his hand to answer a question about world geography in a virtual classroom while his father looks on via his iPad. Valerie Plesch for The New York TimesFloreo lessons are designed to help autistic children build social skills and train for real world experiences like going to the grocery store. Valerie Plesch for The New York TimesAutistic self-advocates note that behavioral therapy to treat autism is controversial among those with autism, arguing that it is not a disease to be cured and that therapy is often imposed on autistic children by their non-autistic parents or guardians. Behavioral therapy, they say, can harm or punish children for behaviors such as fidgeting. They argue that rather than conditioning autistic people to act like neurotypical individuals, society should be more welcoming of them and their different manner of experiencing the world.“A lot of the mismatch between autistic people and society is not the fault of autistic people, but the fault of society,” said Zoe Gross, the director of advocacy at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. “People should be taught to interact with people who have different kinds of disabilities.”Mr. Ravindran said Floreo respected all voices in the autistic community, where needs are diverse. He noted that while Floreo was used by many behavioral health providers, it had been deployed in a variety of contexts, including at schools and in the home.“The Floreo system is designed to be positive and fun, while creating positive reinforcement to help build skills that help acclimate to the real world,” Mr. Ravindran said.In 2017, Floreo secured a $2 million fast track grant from the National Institutes of Health. The company is first testing whether autistic children will tolerate headsets, then conducting a randomized control trial to test the method’s usefulness in helping autistic people interact with the police.Early results have been promising: According to a study published in the Autism Research journal (Mr. Ravindran was one of the authors), 98 percent of the children completed their lessons, quelling concerns about autistic children with sensory sensitivities being resistant to the headsets.Ms. Gross said she saw potential in virtual reality lessons that helped people rehearse unfamiliar situations, such as Floreo’s lesson on crossing the street. “There are parts of Floreo to get really excited about: the airport walk through, or trick or treating — a social story for something that doesn’t happen as frequently in someone’s life,” she said, adding that she would like to see a lesson for medical procedures.However, she questioned a general emphasis by the behavioral therapy industry on using emerging technologies to teach autistic people social skills. A second randomized control trial using telehealth, conducted by Floreo using another N.I.H. grant, is underway, in hopes of showing that Floreo’s approach is as effective as in-person coaching.But it was those early successes that convinced Mr. Ravindran to commit fully to the project.“There were just a lot of really excited people.,” he said. “When I started showing families what we had developed, people would just give me a big hug. They would start crying that there was someone working on such a high-tech solution for their kids.”Clinicians who have used the Floreo system say the virtual reality environment makes it easier for children to focus on the skill being taught in the lessons, unlike in the real world where they might be overwhelmed by sensory stimuli.Celebrate the Children, a nonprofit private school in Denville, N.J., for children with autism and related challenges, hosted one of the early pilots for Floreo; Monica Osgood, the school’s co-founder and executive director, said the school had continued to use the system.“When I started showing families what we had developed, people would just give me a big hug,” said Mr. Ravindran.Valerie Plesch for The New York TimesShe said putting on the virtual headset could be very empowering for students, because they were able to control their environment with slight movements of their head. “Virtual reality is certainly something that is a real gift for our students that we will continue to use,” she said.Kelly Rainey, a special instruction manager with the Cuyahoga County Board of Developmental Disabilities in Ohio, said her organization had used Floreo over the past year to help students with life and social skills. Her colleague Holly Winterstein, an early childhood intervention specialist, said the tools were more effective than the conversation cards typically used by therapists. The office started out with two headsets but quickly purchased equipment for each of its eight staff members.“I do see infinite possibilities,” Ms. Winterstein said.“Social skills from Floreo are sticking,” said Michea Rahman, a speech language pathologist who focuses on underserved populations in Houston (and a Floreo customer). The system “is probably one of the best or the best social skills tool I have ever worked with.” (She added that 85 percent of her patients are Medicaid-based.)To date, the company has raised roughly $6 million. Investors include LifeForce Capital, a venture capital firm focusing on health care software, and the Autism Impact Fund, an early-stage venture capital fund that invests in companies addressing neurological conditions. (Mr. Ravindran declined to specify if the company was profitable.)For Mr. Ravindran, the company has become a mission. “When I started exploring virtual reality as a therapy modality, I didn’t know if it was a hobby project, or if it was going to be a business that I put a little bit of money behind, hired some people, then went off to do something else,” he said. “At some point, I got to this place where if felt, if I don’t build it, no one would.”

Read more →