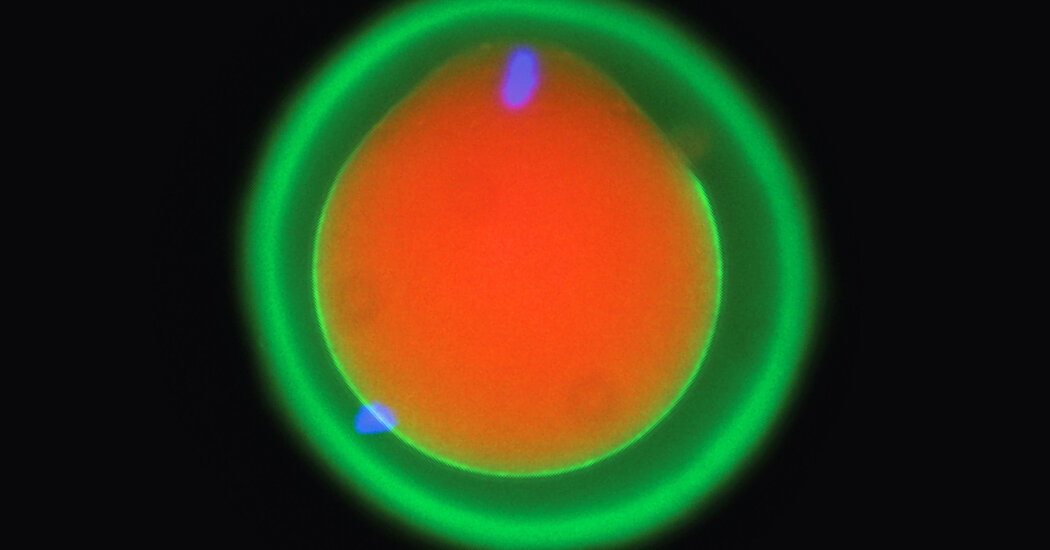

As cephalopods become more important in neuroscience and other fields, scientists and welfare advocates seek to give the smart animals the same protections as mice and monkeys.Lab rats have rights. Before researchers in the United States can experiment on the animals, they need approval from committees that ensure they follow federal regulations for housing and handling the creatures humanely. The same is true of scientists working with mice, monkeys, fish or finches.These protected animals share one thing in common: a backbone.But invertebrates in research labs, including worms and bees or cephalopods like squid and octopuses, do not receive the same protections from the federal government. As researchers are more often working with cephalopods to answer questions in neuroscience and other fields, the matter of whether they’re treating the animals humanely is becoming more pressing.Governments in Europe and Australia have written these smart, spineless animals into their laws. But in the United States, “If you were in a research setting, and you wanted to buy some octopuses and do whatever you wanted to do with them, there is no regulatory oversight to stop you,” said Robyn Crook, a neuroscientist at San Francisco State University.That’s not to say cephalopod research is the wild west. American research institutions are increasingly opting to subject their cephalopod studies to the same approval process as experiments on mice or other vertebrates. But the lack of cephalopod care standards to guide their decisions, combined with the lack of federal oversight to back them up, reflects how rules and laws are lagging behind scientific understanding of these animals’ complex inner lives.🐙🔬🥼Like a lab rat, an octopus can learn to navigate a maze. Octopuses can also perform clever feats that rats can’t, such as disguising themselves as rocks and snakes, breaking out of their tanks or hiding inside coconut shells.In 2021, Alexandra Schnell, a biologist at the University of Cambridge, and others found that cuttlefish can pass a version of the marshmallow test, a famous measure of self-control in human psychology. The cephalopods resisted eating a piece of prawn for as long as two minutes to earn an even better snack (a live shrimp).Unlike humans — whose intelligence is, as it were, all in their heads — octopuses carry the bulk of their nervous system in their arms. Their suckers don’t just grab onto things, they feel and taste them, too. “It’s like if your hands were coated with tongues,” said Christine Huffard, a biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research InstIn one experiment, octopuses were found to stroke a wound with their beaks, and avoid chambers where they were placed after receiving a painful injection.Blickwinkel/AlamyIn a paper published in July, Dr. Huffard and Peter Morse, of James Cook University in Australia showed that male blue-ringed octopuses could use touch to recognize females they’d already mated with. After bumping into a former mate, the males fled, perhaps to avoid being eaten. Such research suggests that octopuses and other cephalopods are smart and sensitive.But do they feel pain like we do? It isn’t just a hypothetical concern. Some research with cephalopods involves potentially painful surgeries, such as amputating an octopus’s arm. We can’t simply ask them whether it hurts, though.“Whether or not pain experience exists in animals outside vertebrates is quite a controversial proposition,” Dr. Crook said. In a 2021 paper, she showed that octopuses that had received an injection of acetic acid had stroked the wound with their beaks and had avoided a chamber where they’d stayed after receiving the injection. But the octopuses had liked being in a chamber where they had experienced a numbing injection after the first one.Researchers use a similar test in rodents to judge whether drugs cause them pain. “We suggest that octopuses feel, and are capable of feeling, the same thing,” Dr. Crook said.In another 2021 paper, she and co-authors studied the nerve activity of octopuses and cuttlefish that had been anesthetized — or so the scientists thought. They’d dipped the animals in magnesium chloride to anesthetize them, a common lab procedure. When an animal stopped moving and turned white, scientists had assumed it couldn’t feel anything and wouldn’t be stressed by handling. But electrode recordings showed that for several minutes after becoming unresponsive, the cephalopod could still feel experimenters touching its body.Dr. Crook said the finding immediately changed how researchers in her lab anesthetized octopuses. Now, they wait as long as 20 extra minutes to make sure the animals won’t feel anything. She hopes other labs have changed their practices, too.🐙🔬🥼Who’s responsible for the well-being of captive animals? The answer, in the United States, is complicated.The Animal Welfare Act, passed in 1966, requires humane treatment of animals such as primates and pet dogs and cats. It doesn’t apply to farm animals, racehorses, invertebrates, fish, or lab rats or mice. Another law, the Health Research Extension Act of 1985, governs the treatment of all vertebrate animals in research funded by the U.S. government.Both laws require universities and other research institutions to have an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, or IACUC. Committees must include at least one veterinarian and one person unaffiliated with the institution. Before starting a research project, a scientist must submit a proposal to their institution’s committee, which, in turn, must make sure the scientist’s plan meets federal guidelines.“I think it works well,” said Dr. Steve Niemi, a lab animal veterinarian and director of the Animal Science Center at Boston University. “This is both a highly contentious area and a highly scrutinized — and, I would argue, highly regulated — area” for vertebrates, Dr. Niemi said.Male blue-ringed octopuses were found to recognize females they’ve already mated with by their sense of touch, a sign of how sensitive their limbs are.Norbert Probst/AlamyDr. Niemi said critics have pointed out that animal care committees have rarely denied approval to researchers. But in his experience, this is because committees go back and forth with a scientist to revise the plan until it is acceptable. “To me, our mission is to enable responsible research,” he said.As scientists learn more about cephalopods’ intelligence and perception of pain, Dr. Niemi said, “It is incumbent upon us ethically to consider if, and how, to add them to our local oversight.”Already, many universities are voluntarily having their committees review research on cephalopods. Dr. Crook said that this trend has gained momentum in the past two years.However, she said, the job of these committees is to make sure researchers are following federal law, but when it comes to invertebrates, that law doesn’t exist. “They’re almost operating unanchored,” she said.There’s also no universal manual for cephalopod care because scientists are still learning about their biology. In the event that a researcher violated their agreement with the committee, for example, there could be no legal recourse to stop their experiment from happening.“In some ways, it’s regulation theater,” Dr. Crook said.🐙🔬🥼While universities and other research institutions try to apply a nonexistent law to their cephalopods, Katherine Meyer, who directs the Animal Law and Policy Clinic at Harvard Law School, is trying to pressure the National Institutes of Health, the main federal funder of biomedical research in the United States, into making a change.In 2020, Ms. Meyer’s clinic petitioned the institutes’ Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare to take action toward regulating cephalopod research. “I just had the idea that we should do something to protect octopuses,” she said.Ms. Meyer realized that while the 1985 Health Research Extension Act addressed the care of “animals in research,” it didn’t actually define an animal. The definition of animals as “live, vertebrate” creatures is in another N.I.H. document called the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.“That’s when I saw the opening,” Ms. Meyer said. She said the N.I.H.’s lab animal office could protect octopuses and their kin by simply changing the definition of “animals” in the policy to include cephalopods, rather than amending the underlying law.She received a response in July 2020 that said the agency was “aware of the standards in other countries that include cephalopods in animal welfare oversight and regulations” and was “currently considering options for providing guidance on humane care and use of invertebrates in N.I.H. funded research.”Beyond that, she said, “We have not gotten a substantive response from the agency.”“An unhealthy and overly stressed octopus isn’t going to yield useful data,” Dr. Huffard said. Terry Moore/Stocktrek Images, via AlamyIn response to a request for comment, a spokesperson for the N.I.H. Office of Extramural Research repeated the language from Ms. Meyer’s letter.Dr. Huffard said that in the absence of new federal guidance, many international scientific journals require U.S. researchers to show that they’ve passed cephalopod research through an IACUC or another institutional review process before their research can be published. An animal-welfare nonprofit called AAALAC International, which offers voluntary accreditation to research institutions, is also recommending that institutional committees approve cephalopod research.“I don’t know any cephalopod researcher that would just scoff at these rules,” Dr. Huffard said. Even if the U.S. government hasn’t determined that cephalopods deserve the same protections as other animals, scientists who study the many-armed creatures have made that determination for themselves.“An unhealthy and overly stressed octopus isn’t going to yield useful data,” Dr. Huffard said. Even aside from the data, she added, “I want the animals to be happy and healthy.”As long as we’re rethinking how our laws privilege animals with backbones, through, Dr. Huffard said it may not make sense to elevate cephalopods above the other spineless species. Octopuses “are very complex animals; nobody will doubt that,” she said. “Are they the most complex invertebrates? Depends on how you define that.”Bees, for instance, have remarkably intricate behaviors and social structures. Crabs and lobsters were recently declared sentient by the British government, and in Switzerland, it’s illegal to boil a lobster alive. “If people studied mantis shrimps the way they study octopuses, they would be really blown away at how smart they are,” Dr. Huffard said.“I feel like we should be treating all animals with that level of respect,” she said.

Read more →