Cough-syrup scandal: How did it end up in The Gambia?

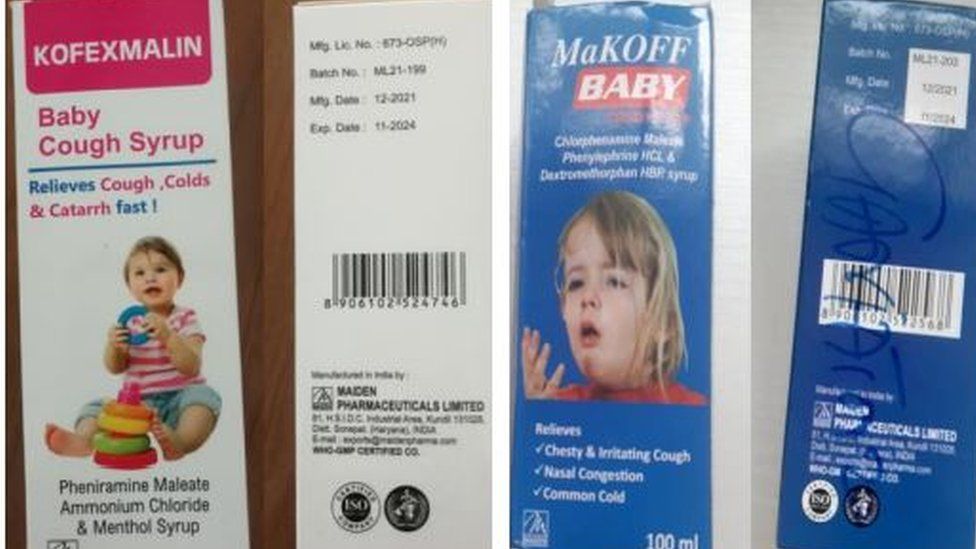

Published9 hours agoSharecloseShare pageCopy linkAbout sharingImage source, WHOBy Shruti MenonBBC Reality CheckThe deaths of nearly 70 children in The Gambia, linked to cough syrups made in India, are being investigated amid concerns about effective regulation of the manufacture and trade in medicines. What went wrong in The Gambia? Last week, the World Heath Organization (WHO) issued a global alert over four brands of cough syrups, saying they could be linked to acute kidney damage, following reports from The Gambia of children diagnosed with serious kidney problems.Laboratory analysis of the syrups “confirms that they contain unacceptable amounts of diethylene glycol and ethylene glycol as contaminants”, according to the WHO. The Indian authorities and the cough syrup manufacturer, Maiden Pharmaceuticals, say these syrups have been exported to The Gambia only.Image source, Getty ImagesWhat is known about the manufacturer?Maiden Pharmaceuticals says it adheres to internationally recognised quality-control standards.But some of its products have failed to meet national or state-level quality-control standards in India. Official records there show the company: was blacklisted by Bihar state, in 2011, for selling a syrup failing to meet local standardswas subject to legal proceedings by India’s drug regulator, in 2018, for quality-control violationsfailed a quality-control test in Jammu and Kashmir state, in 2020has failed quality-control tests in Kerala state four times in 2022It is also among nearly 40 Indian pharmaceutical companies blacklisted by Vietnam for exporting sub-standard products.The company, based in Haryana state, has said it is “shocked” by the deaths in The Gambia and had “been diligently following the protocols of the health authorities, including [the] drugs controller general [of India] and the state drugs controllers, Haryana”.We’re not selling anything in domestic market. We’ve been obtaining raw materials from certified & reputed companies. CDSCO officials have taken samples & we are awaiting the results: Maiden Pharmaceuticals Ltd on deaths of 66 children in Gambia allegedly due to their cough syrup pic.twitter.com/HFEJbx1POx— ANI (@ANI) October 8, 2022

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.View original tweet on TwitterIt would not comment further while drugs regulators were still testing, it added.Haryana Health Minister Anil Vij told BBC News samples had been sent for testing and if something wrong was detected, action would be taken.How effective is India’s quality control?India produces a third of the world’s medicines, mostly in the form of generic drugs. It is a major supplier to countries in Africa, Latin America and other parts of Asia. Image source, Getty ImagesIts manufacturing plants are required to adhere to stringent quality-control standards and production practices. But Indian companies have faced criticism and even bans by overseas regulators such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for quality-control problems at some plants.One analysis of India’s pharmaceutical industry points to underfunding of oversight bodies and a lax interpretation of regulations as key issues, with a lack of interest in ensuring purity standards are adhered to.Public-health activist Dinesh Thakur also highlights the relatively light punishment in India for flouting quality standards – a fine of $242 (£220) and a possible prison sentence of up to two years.”Unless one can causally establish a direct link between a sub-standard drug and a fatality, this is the norm of punishment meted out,” he says. Also, India is not included in the WHO standards for national bodies that regulate medicines, although it is for vaccines.”This may result in inconsistent regulatory control over pharmaceutical manufacturing activities,” Leena Menghaney, head of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Access Campaign South Asia, says.Should The Gambia have tested?The Health Ministry in Delhi has launched an investigation but says it is “usual practice that the importing country tests these imported products… and satisfies itself as to the quality”.But The Gambia’s Medicine Control Agency executive director Markieu Janneh Kaira says it prioritises checks on anti-malarial drugs, antibiotics and painkillers, rather than cough syrup.BBC News contacted the agency for clarification but had no response.The Gambia’s President, Adama Barrow, has said he “would get to the bottom” of the causes of the tragedy and announced the creation of “a quality-control national laboratory for drugs and food safety”.The Gambia would “establish safeguards to eliminate the importation of sub-standard drugs”, he added.MSF wants countries with sufficient testing capacity to help low-income countries such as The Gambia. “This is not about the importing countries responsibility only,” Ms Menghaney says.In Nigeria, the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control is now asking for all imported shipments of pharmaceuticals to be cleared by approved agents prior to leaving India. Read more from Reality CheckSend us your questions