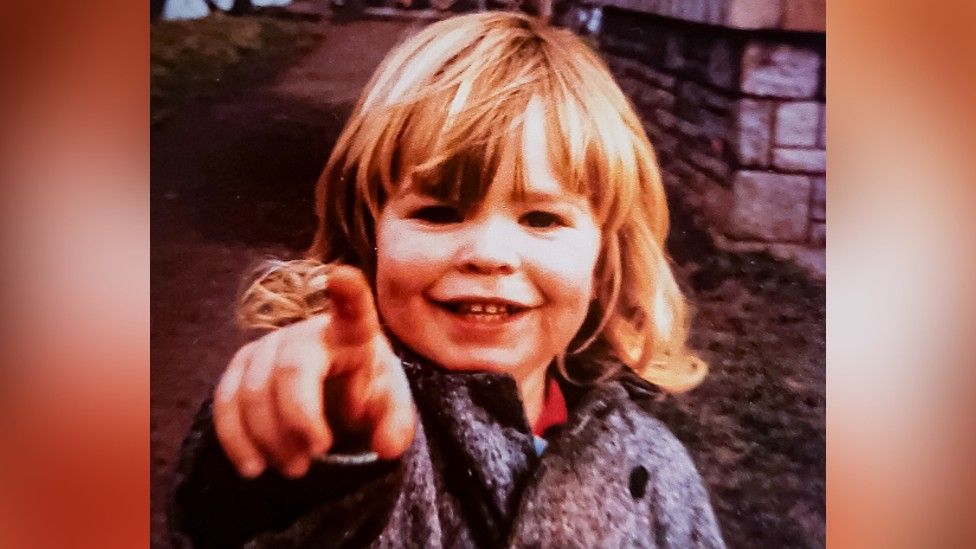

Published10 hours agoShareclose panelShare pageCopy linkAbout sharingImage source, Allan ArchiveBy Chloe Hayward and Hugh PymHealth producer and health editor, BBC NewsThe true scale of the number of medical trials using infected blood products on children in the 1970s and 80s has been revealed by documents seen by BBC News.They reveal a secret world of unsafe clinical testing involving children in the UK, as doctors placed research goals ahead of patients’ needs.They continued for more than 15 years, involved hundreds of people, and infected most with hepatitis C and HIV.One surviving patient told the BBC he was treated like a “guinea pig”.The trials involved children with blood clotting disorders, when families had often not consented to them taking part. The majority of the children who enrolled are now dead. Documents also show that doctors in haemophilia centres across the country used blood products, even though they were widely known as likely to be contaminated.A shortage of blood products in the UK in the 1970s and 80s meant they were imported from the US. High-risk donors such as prisoners and drug addicts provided the plasma for the treatments that were infected with potentially fatal viruses including hepatitis C – which attacks the liver resulting in cirrhosis and cancer – and HIV. One blood product, known as Factor VIII, was seen to be highly effective for stopping bleeding but also widely known to be contaminated with viruses. A public inquiry is under way into the scandal. The final report is due in May. ‘Guinea pig’Luke O’Shea-Phillips, 42, has mild haemophilia – a blood clotting disorder that means he bruises and bleeds more easily than most. He caught the potentially lethal viral infection hepatitis C while being treated at the Middlesex Hospital, in central London, which was administered because of a small cut to his mouth, aged three, in 1985.Documents seen by the BBC suggest he was deliberately given the blood product – which his doctor knew might have been infected – so he could be enrolled in a clinical trial.The doctor wanted to find out how likely patients were to catch diseases from a new version of heat-treated Factor VIII. Though he had never been treated for his condition before, Luke was given heat-treated Factor VIII to stop his mouth bleeding.A letter from Luke’s doctor, Samuel Machin, to another expert in haemophilia, was submitted in evidence to the public inquiry into the infected blood scandal.Writing to Peter Kernoff, at London’s Royal Free Hospital, Dr Machin detailed the treatment of Luke and another boy, asking: “I hope they will be suitable for your heat-treated trial.”Months earlier, Dr Kernoff had called on fellow doctors in the field to identify patients suitable for clinical trials. Specifically, he said, they had to be “previously untreated patients”, known as “PUPs” in the medical community. They were also nicknamed “virgin haemophiliacs” – a term written on Luke’s medical record by Dr Machin.”I was a guinea pig in clinical trials that could have killed me,” Luke told the BBC. “There is no other way to explain it – my treatment was changed so I could be enrolled in clinical trials. This change in medication gave me a fatal disease – hepatitis C – yet my mother was never even told.””To the scientific world, it was an incredible benefit being a virgin haemophiliac,” he added. “To be a clean petri dish to understand science through, I was without question a part of that.”What is the infected blood scandal?Parents and pupils kept in the dark at blood scandal schoolInfected blood scandal: Boy, 7, died from Aids after doctor ignored rules In the following years, as the medical trial reached its conclusions, Luke had many blood tests. Doctors said they were monitoring him and, at the time, his mother, Shelagh O’Shea, was grateful. In their findings, published in 1987, Dr Kernoff and Dr Machin concluded heat treatment had “little or no effect” in reducing the risk of hepatitis C. Both Dr Kernoff and Dr Machin are now dead.Before he died, Dr Machin gave evidence to the public inquiry, when he confirmed that Luke had been recruited to Dr Kernoff’s study.He denied this had been done without Luke’s mother’s knowledge. “This would have been discussed with his mother, although I acknowledge that standards of consent in the 1980’s was quite different to what it is now,” Dr Machin said.However, Mrs O’Shea told the inquiry she was “absolutely not” told about the trial. “With an innocent child of three and a half I would not have considered such an action. I would never ever have allowed my child to be part of a trial – never,” she added.Documents reveal doctors knew Luke had contracted hepatitis C as early as 1993, but he was not told until 1997. One medical record states a positive test result and says: “Have not discussed with patient or family.”Luke is now clear of the infection after successful treatment.’Laboratory rats’However, evidence of the clinical trials have raised wider concerns. “A patient should always be given the best possible treatment and they should always have given informed consent – if those two factors haven’t been achieved then a trial would be seen as very problematic,” says Professor Emma Cave, Professor of Healthcare Law at Durham University.Professor Edward Tuddenham, who was a haemophilia doctor at the Royal Free Hospital in the 1980s, confirmed these fears. When asked if he thought ethical standards had been met during clinical trials in the 1980s, he simply answered: “No.”The BBC’s investigation has revealed that Dr Machin and Dr Kernoff were among a community of doctors with similar research ambitions.A specialist school near Alton, in Hampshire, was attended by a large cohort of haemophiliac boys. The school for disabled children had an NHS haemophilia unit on site, so boys who had bleeds could be treated quickly and then return to lessons. Their doctor, Dr Anthony Aronstam – who has also since died – used his “unique” cohort of boys for extensive clinical trials. One series of experiments considered whether using three to four times more Factor VIII than normally required by a child would help to reduce the number of bleeds he had. This was preventative treatment, know as prophylaxis, and involved repeated injections with infected Factor VIII products and follow-up blood tests. The high concentrations of infected blood products were administered to the boys without their – or their parents’ – consent. Of the122 pupils attending Treloar’s College between 1974-1987, 75 have so far died of HIV and hepatitis C infections.”Despite knowing the product was riddled with hepatitis, they started a trial that required us to have way more of it than we needed,” says Gary Webster, who was unknowingly enrolled.Ade Goodyear, a pupil at Treloar’s from 1980 to 1989, added: “We were treated like lab rats. There was a plethora of studies that we were all enrolled on for the decade we were at the school.”Image source, Lee StayControversially, another trial involved placebo treatments. This meant that some boys, who thought they had been given Factor VIII to prevent bleeds, had in fact been given a saline solution.”When you think you’ve been given a treatment, this changes your behaviour,” Gary said. “You run more, you play more rough in football. For a haemophiliac, you feel a bit invincible for a short window after a jab. But with a placebo you are just risking your life by changing your behaviour.”He told the BBC he was punished at school if he missed injections. “It would have meant their trials would have been flawed and so we, us kids, were made to toe the line.”Dr Kernoff’s pursuit of clinical advancement through research was rigorous, as was his hunt for suitable subjects for trials – PUPs and virgin haemophiliacs – which led to those involved getting young and younger. A four-month-old baby was involved in a trial. Among his studies was one that compared the infectiousness of another blood plasma product – Cryoprecipitate (Cryo) – to Factor VIII concentrates.Cryo was used for treating mild blood clotting conditions. It contained the Factor VIII protein, but at lower concentrations and from fewer donors and was therefore thought to be less risky.Dr Kernoff’s search for suitable subjects led him to Mark Stewart, his brother, and his father, who all had very mild cases of von Willebrand’s disease – another type of blood clotting disorder. Their usual treatment was cryo.Image source, Mark Stewart As part of his test, Dr Kernoff gave them all Factor VIII concentrates instead.”Until we were given concentrates it would be once a month you’d have a little nose bleed, and you’d go up and have cryo and that was that.” All three contracted hepatitis C.Mark’s brother and father have both died of liver cancer after the infection attacked the organ. Neither were told they had contracted the disease until it was too late for treatment.”Angry is an understatement,” Mark said. “Your dad is in the front carriage, your brother is in the second carriage and you are in the third carriage – so you know what is coming. It won’t veer off that track. This is how hep C works. It will get you.”A statement from Treloar’s said: “We await the publication of the infected blood inquiry, which we hope will provide our former pupils with the answers they have been waiting for.”The inquiry into the wider infected blood scandal will conclude on 20 May.More on this storyWhat is the infected blood scandal and how many people died?Published2 AprilBoy, 7, died from Aids after doctor ignored rulesPublished5 days agoInfected blood inquiry report delayed until MayPublished17 JanuaryAction lodged against school over infected bloodPublished24 January 2022Parents and pupils kept in dark at infected blood schoolPublished26 June 2021The school where dozens died in NHS blood scandalPublished21 June 2021Related Internet LinksInfected Blood InquiryThe BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.

Read more →