Heart-Valve Patients Should Have Earlier Surgery, Study Suggests

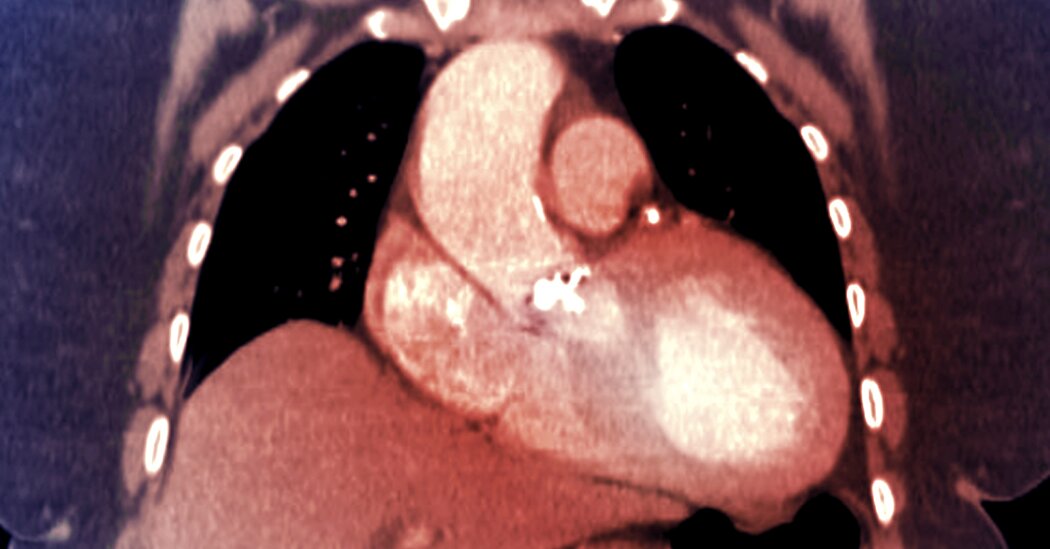

The results of a new clinical trial have overturned the “wait and see” approach that cardiologists have long favored for symptom-free patients.For decades, people with failing heart valves who nevertheless felt all right would walk out of the cardiologist’s office with the same “wait and see” treatment plan: Come back in six or 12 months. No reason to go under the knife just yet.A new clinical trial has overturned that thinking, suggesting that those patients would be much better off having their valves replaced right away with a minimally invasive procedure.The trial, whose results were published this week in The New England Journal of Medicine, could change the way doctors treat severe aortic stenosis, a narrowing of the valve that controls blood flow from the heart. The disease, which has a prognosis worse than that of most cancers, afflicts more than 3 percent of people ages 65 and older. It is expected to become more common as people live longer.Replacing people’s heart valves, even if they were not yet experiencing any ill effects, appeared to roughly halve their risk of being unexpectedly hospitalized for heart problems over at least two years, the trial found.Patients who were put on the more conservative treatment plan overwhelmingly ended up needing surgery anyway: Roughly 70 percent of them developed symptoms and needed to have their valves replaced within two years, suggesting that the disease worsens more quickly than previously understood.“You may be able to at least prevent that progression and perhaps improve patient outcomes by treating earlier,” said Dr. Gregg Stone, a professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, describing the implications of the trial. The findings, he said, “will have a major effect on practice.”We are having trouble retrieving the article content.Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.Thank you for your patience while we verify access.Already a subscriber? Log in.Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Read more →