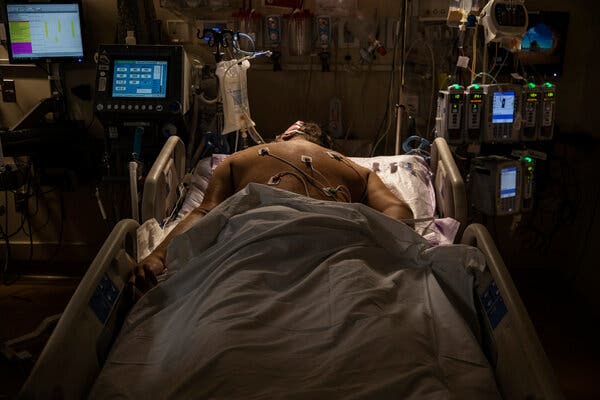

The small Midwestern gender clinic was buckling under an unrelenting surge in demand.Last year, dozens of young patients were seeking appointments every month, far too many for the clinic’s two psychologists to screen. Doctors in the emergency room downstairs raised alarms about transgender teenagers arriving every day in crisis, taking hormones but not getting therapy.Opened in 2017 inside a children’s hospital affiliated with Washington University in St. Louis, the prestigious clinic was welcomed by many families as a godsend. It was the only place for hundreds of miles where distressed adolescents could see a team of experts to help them transition to a different gender.But as the number of these patients soared, the clinic became overwhelmed — and soon found itself at the center of a political storm. In February, Jamie Reed, a former case manager, went public with explosive allegations, claiming in a whistle-blower complaint that doctors at the clinic had hastily prescribed hormones with lasting effects to adolescents with pressing psychiatric problems.Ms. Reed’s claims thrust the clinic between warring factions. Missouri’s attorney general, a Republican, opened an investigation, and lawmakers in Missouri and other states trumpeted her allegations when they passed a slew of bans on gender treatments for minors. L.G.B.T.Q. advocates have pointed to parents who disputed her account in local news reports and to a Washington University investigation that determined her claims were “unsubstantiated.”The reality was more complex than what was portrayed by either side of the political battle, according to interviews with dozens of patients, parents, former employees and local health providers, as well as more than 300 pages of documents shared by Ms. Reed.Some of Ms. Reed’s claims could not be confirmed, and at least one included factual inaccuracies. But others were corroborated, offering a rare glimpse into one of the 100 or so clinics in the United States that have been at the center of an intensifying fight over transgender rights.The turmoil in St. Louis underscores one of the most challenging questions in gender care for young people today: How much psychological screening should adolescents receive before they begin gender treatments?Shaped by ideas pioneered in Europe, these clinics have opened over the past decade to serve the growing number of young people seeking hormonal medications to transition. Many patients and parents told The New York Times that the St. Louis team provided essential care, helping adolescents feel comfortable in their bodies for the first time. Some patients said they were lifted out of grave depression.A rally at the Missouri Statehouse in Jefferson City, Mo., in March.Charlie Riedel/Associated PressBut as demand rose, more patients arrived with complex mental health issues. The clinic’s staff often grappled with how best to help, documents show, bringing into sharp relief a tension in the field over whether some children’s gender distress is the root cause of their mental health problems, or possibly a transient consequence of them.With its psychologists overbooked, the clinic relied on external therapists, some with little experience in gender issues, to evaluate the young patients’ readiness for hormonal medications. Doctors prescribed hormones to patients who had obtained such approvals, even adolescents whose medical histories raised red flags. Some of these patients later stopped identifying as transgender, and received little to no support from the clinic after doing so.Unwanted outcomes and regrets happen in every branch of medicine, but several clinics around the world have reported challenges similar to those in St. Louis. Pediatric gender medicine is a nascent specialty, and few studies have tracked how patients fare in the long term, making it difficult for doctors to judge who is likely to benefit.In several European countries, health officials have limited — but not banned — the treatments for young patients and have expanded mental health care while more data is collected. In the United States, health groups have endorsed what’s known as affirming care even as their peers in Europe have grown more cautious. And conservative lawmakers in more than 20 states have taken the draconian step of banning or severely restricting gender treatments for minors.Civil rights groups are challenging the Missouri ban in a hearing this week, and Ms. Reed testified on Tuesday in favor of it, describing her allegations in detail.Washington University created an oversight committee to carry out weekly reviews of the gender clinic’s operations. The school’s investigation claimed that none of the clinic’s 598 patients on hormonal medications reported “adverse physical reactions.” In a statement to The Times, the university said that it would not address specific allegations because of patient privacy, and that “physicians and staff have treated patients according to the existing standard of care.”But doctors in St. Louis and elsewhere are wrestling with evolving standards and uncertain scientific evidence — all while facing intense political pressure and an adolescent mental health crisis.An Affirming ApproachKim Hutton, a founder of a parents group called TransParent. “In Missouri there were no knowledgeable doctors on this subject,” she said. “It was left to the parents to try to figure it out.”Bryan Birks for The New York TimesAmerica’s first youth gender center opened in Boston, in 2007, after two clinicians — Dr. Norman Spack, an endocrinologist, and Laura Edwards-Leeper, a child psychologist — traveled to the Netherlands to observe a promising treatment for children with gender distress, known as dysphoria.The Dutch doctors were prescribing drugs that stalled puberty in order to prevent the physical changes that often exacerbate dysphoria. The approach, they reasoned, would give the adolescents time to consider whether to proceed with estrogen or testosterone treatments later on.Transgender children have high rates of anxiety, depression and suicide attempts. The Dutch found that for a specific group — adolescents with no severe psychiatric disorders who had experienced gender dysphoria since early childhood — their depression lessened after taking puberty blockers.When Dr. Spack and Dr. Edwards-Leeper opened the Boston clinic, they hewed closely to the Dutch approach. In its first five years, the clinic treated just 70 patients.Similar clinics opened around the country, diverging over time from the strict Dutch protocols into an affirming approach that prioritized a child’s inner sense of gender. It was unethical, some argued, to deny care to children with psychiatric problems when gender treatments could help resolve those issues.In 2012, parents in St. Louis began lobbying leaders of the children’s hospital to set up an affirming clinic. The parents invited Dr. Spack to town to talk about his experience in Boston.“In Missouri there were no knowledgeable doctors on this subject,” said Kim Hutton, a founder of the group, called TransParent. “It was left to the parents to try to figure it out.”The clinic opened in 2017, led by Dr. Christopher Lewis, a pediatric endocrinologist, and Dr. Sarah Garwood, an adolescent medicine specialist, who had each attended TransParent meetings. They saw patients once a week on the second floor of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital, spending most days elsewhere in the sprawling complex.When Ms. Reed arrived, in 2018, she was the clinic’s only full-time employee. Eventually, the clinic would have about nine staff members, most part-time.Their patients were part of a striking generational change: Between 2017 and 2020, about 1.4 percent of 13- to 17-year-olds in the United States identified as transgender, nearly double the rate from a few years earlier.It’s clear the St. Louis clinic benefited many adolescents: Eighteen patients and parents said that their experiences there were overwhelmingly positive, and they refuted Ms. Reed’s depiction of it. For example, her affidavit claimed that the clinic’s doctors did not inform parents or children of the serious side effects of puberty blockers and hormones. But emails show that Ms. Reed herself provided parents with fliers outlining possible risks.Ms. Hutton’s son, who requested anonymity because of privacy concerns, is now in college, and said he was grateful he transitioned years earlier. “I have normal-people problems, which is all that I ever wanted,” he said.Another patient, Chris, now 19, who also requested anonymity to protect his privacy, recalled Dr. Lewis patiently drawing diagrams on the paper sheet of his exam chair, explaining how testosterone would redistribute his body fat and permanently deepen his voice. Chris felt “drastically improved” after taking the hormone, he said, but was still distressed by his breasts. At 17, he went to a surgeon in Ohio for a mastectomy.And Becky Hormuth, a teacher in St. Charles, Mo., praised the center’s doctors for their approach to her son’s mental health. The doctors diagnosed her 15-year-old with autism, she said, and connected him with a dietitian to help treat his eating disorder — before prescribing testosterone. Now, at 16, her son is “better than he’s ever been,” Ms. Hormuth said.A family therapist in St. Louis, Katie Heiden-Rootes, said she had worked with or supervised the counseling of roughly 30 of the clinic’s patients and had never seen problems with their care.“The biggest complaint I heard about the clinic was, ‘We can’t get in,’” Dr. Heiden-Rootes said.Katie Heiden-Rootes, a family therapist, said she had counseled about 30 of the clinic’s patients and had never seen problems with their care.Bryan Birks for The New York TimesBecky Hormuth’s son is a patient at the St. Louis clinic. “I’m worried everything we’ve fought for for our kid is going to come crumbling down,” she said.Bryan Birks for The New York TimesThe Red Flag ListWhen Ms. Reed, 43, began working at the clinic, she considered herself a fierce champion of the gender-affirming model. In her previous jobs — at Planned Parenthood, at an H.I.V. clinic and in the foster care system — she had also supported L.G.B.T.Q. young people. And her husband, a transgender man, had shown her how essential gender-affirming care could be.Ms. Reed’s job at the clinic was akin to that of a social worker — collecting medical histories, triaging appointments and supporting patients in the hospital, at school and in court.Her doubts about the affirming model arose in 2019, she said, after hearing from an upset patient who regretted their medical transition. She grew more concerned in 2020 as more new patients sought the clinic’s help, many with psychological problems exacerbated by the pandemic. She saw parallels with England’s youth gender clinic, known as the Tavistock, which was under investigation after employees complained about feeling pressure to approve children for puberty blockers as their wait-list swelled.The St. Louis center relied heavily on outside therapists to vet patients, emails show. Doctors there prescribed hormones to patients who had identified as transgender for at least six months, had received a letter of support from a therapist and had parental consent.Frustrated that the clinic had no system to keep track of patient outcomes, Ms. Reed and the clinic’s nurse, Karen Hamon, kept a private spreadsheet, which they called the “red flag list.” (Ms. Reed gave The Times a version of the spreadsheet without identifying information. Ms. Hamon and other clinic employees declined to comment for this article.)The list eventually included 60 adolescents with complex psychiatric diagnoses, a shifting sense of gender or complicated family situations. One patient on testosterone stopped taking schizophrenia medication without consulting a doctor. Another patient had visual and olfactory hallucinations. Another had been in an inpatient psychiatric unit for five months.On a different tab, they tallied 16 patients who they knew had detransitioned, meaning they had changed their gender identity or stopped hormone treatments.Ms. Reed saw parallels with England’s youth gender clinic, known as the Tavistock, which was under investigation after employees complained about feeling pressure to approve children for puberty blockers.Peter Nicholls/ReutersOne patient emailed the clinic, in January 2020, to say they had detransitioned and were seeking a voice coach for their masculinized voice. They also requested a referral for an autism screening, noting, “I have mentioned this before at appointments and over email, but it did not seem to go anywhere.”In another email thread, the center’s staff discussed a patient who regretted a recent mastectomy. The patient had messaged their surgeon at Washington University twice about wanting a breast reconstruction, but had not received a reply.The Times independently found another St. Louis patient who detransitioned, Alex, who posted on Reddit last year to “give a warning” about the clinic. (Alex shared medical records with The Times to corroborate her account.)Alex arrived at the center in late 2017 at age 15, she said, after identifying as transgender for three years. She had been referred by a therapist who was treating her for bipolar disorder and anxiety.Alex was prescribed testosterone, she said, after one appointment with Dr. Lewis. “There was no actual speaking to a psychiatrist or another therapist or even a case worker,” she wrote on Reddit.After three years on the hormone, she realized she was nonbinary and told the clinic she was stopping her testosterone injections. The nurse was dismissive, she recalled, and said there was no need for any follow-ups.Alex, now 21, does not exactly regret taking testosterone, she told The Times, because it helped her sort out her identity. But “overall, there was a major lack of care and consideration for me,” she said.The number of people who detransition or discontinue gender treatments is not precisely known. Small studies with differing definitions and methodologies have found rates ranging from 2 to 30 percent. In a new, unpublished survey of more than 700 young people who had medically transitioned, Canadian researchers found that 16 percent stopped taking hormones or tried to reverse their effects after five years. Survey responders reported a variety of reasons, including health concerns, a lack of social support and changes in gender identity.‘Disastrously Overwhelmed’Laura Edwards-Leeper warned in 2021 that American gender clinics were prescribing hormones to some children who needed mental health support first.Kristina Barker for The New York TimesNearly 15 years after bringing the Dutch approach to America, Dr. Edwards-Leeper, the Boston psychologist, had grown alarmed by the rise in adolescents seeking gender treatments.In a November 2021 Washington Post opinion piece, Dr. Edwards-Leeper warned that American gender clinics were prescribing hormones to some children who needed mental health support first.“We may be harming some of the young people we strive to support — people who may not be prepared for the gender transitions they are being rushed into,” she wrote with Erica Anderson, the former president of the U.S. Professional Association for Transgender Health and a transgender woman.In St. Louis, Dr. Andrea Giedinghagen, the clinic’s psychiatrist, emailed the essay to her colleagues. “This basically encapsulates the (very complex, nuanced) views that the child and adolescent psychiatrists I know at various gender centers hold,” Dr. Giedinghagen wrote.The head of the clinic, Dr. Lewis, responded, adding a university administrator to the thread. “I DO think our clinic, and transgender care at large, exhibits some of the concerns mentioned,” he wrote, including being “disastrously overwhelmed.”But, he added, “No matter the approach there will be a percentage of patients that should have been started that weren’t and vice versa.”By the end of 2021, emails show, the clinic was getting calls from four or five new patients every day — a sharp rise from 2018, when it saw that many over the course of a month. And, according to an internal presentation from 2021, 73 percent of new patients were identified as girls at birth. Gender clinics in Western Europe, Canada and the United States have reported a similarly disproportionate sex skew that has bewildered clinicians.St. Louis Children’s Hospital, where the gender clinic opened in 2017. When Ms. Reed arrived in 2018, she was the clinic’s only full-time employee.Bryan Birks for The New York TimesOther parts of the St. Louis hospital were also seeing more transgender patients. In August and September of 2022, Ms. Reed and Ms. Hamon, the clinic’s nurse, conducted a half-dozen training sessions with the emergency department to explain their work at the gender clinic. At the trainings, E.R. staff shared concerns about their own experiences with their young transgender patients, which Ms. Hamon later relayed to her team and university administrators.The E.R. staff, she wrote in an email, had been seeing more transgender adolescents experiencing mental health crises, “to the point where they said they at least have one TG patient per shift.”“They aren’t sure why patients aren’t required to continue in counseling if they are continuing hormones,” Ms. Hamon added. And they were concerned that “no one is ever told no.”As similar mental health issues bubbled up at clinics worldwide, the international professional association for transgender medicine tried to address them by publishing specific guidelines for adolescents for the first time. The new “standards of care,” released in September, said that adolescents should question their gender for “several years” and undergo rigorous mental health evaluations before starting hormonal drugs.Dr. Lewis worried that his clinic would not be able to adjust to the new standards, known as the S.O.C.“Right now I have no idea how to meet what would be the most intensive interpretations of the SOC,” Dr. Lewis texted Ms. Hamon. (She took a screenshot of the message and sent it to Ms. Reed.) He suggested meeting with staff members to discuss how they could abide by the new guidelines.In its statement, the university said that the clinic prioritized mental health care and that licensed external therapists “make a vital contribution to that effort.” It also said that “patients have ongoing relationships with mental health providers.”Some former staff members said the clinic was doing the best it could for patients with complex psychiatric histories. Cate Hensley, a social worker who interned at the clinic from 2020 to 2021, said that the team had a weekly meeting to discuss such cases.She also said that U.S. hospitals and health insurers invested far too little in mental health, putting extra pressure on doctors and hurting patients.“This center is providing ethical care in an unethical system,” Mx. Hensley said.Political AgendasJennifer Harris Dault, a Mennonite pastor, moved her family to New York to ensure that her child could get gender treatments when she nears puberty.Lauren Petracca for The New York TimesBy the end of last year, Republican lawmakers in Missouri had turned gender care for minors into a rallying cry. And Ms. Reed, formerly a staunch defender of the affirming model, had become openly skeptical of it, raising concerns in internal emails and in meetings despite warnings from higher-ups.Her performance review in 2022 stated that she “responds poorly to direction from management with defensiveness and hostility.” In November, she left the gender clinic and started a new role at the university coordinating pediatric cancer research.Ms. Hamon raised doubts as well, according to text messages and emails provided by Ms. Reed. In January of this year, she emailed an administrator to explain why she did not want a management role at the center.“You know I have struggled with ethical dilemmas about how we do things for quite some time,” Ms. Hamon wrote.That month, Ms. Reed obtained a prominent parental rights lawyer, Vernadette Broyles. Shortly thereafter, she filed her complaint with the state and publicized her allegations in an essay in The Free Press. Ms. Broyles is a vocal proponent of gender treatment bans for minors and has said the “transgender movement” poses an “existential threat to our culture.”Ms. Reed said that she supported the rights of transgender adults like her husband, and that Ms. Broyles was the only lawyer who would take her case pro bono. Still, Ms. Reed does not deny that her views have hardened and become political: “I support a national moratorium on the medicalization of kids,” she said.One parent said that, perhaps in pursuit of this political aim, Ms. Reed had misrepresented her child’s experience.Ms. Reed’s affidavit describes a patient whose liver was damaged after taking bicalutamide, a drug that blocks testosterone. It makes a specific claim about what a parent had written to the child’s doctors: “The parent said they were not the type to sue, but ‘this could be a huge P.R. problem for you.’”The parent, Heidi, a data scientist in the St. Louis area who requested anonymity because of privacy concerns, said she was stunned to read this “twisted” description of her teenage daughter’s case.Heidi, a parent in the St. Louis area who requested anonymity, said Ms. Reed misrepresented her child’s experience.Bryan Birks for The New York TimesHeidi’s daughter indeed had liver damage, a rare side effect of bicalutamide. But she had been taking the drug for a year, records show, and had a complicated medical history. She was immunocompromised, and experienced liver problems only after getting Covid and taking another drug with possible liver side effects.In a message to doctors that was shared with The Times, Heidi actually wrote, “In our world, it’s like a P.R. nightmare” — referring to tensions in her family about the gender treatments. The message did not mention anything about suing the clinic. To the contrary, it said: “We don’t regret any decision.”Ms. Reed said that she learned about the case from Ms. Hamon, who helped compile examples for the affidavit, and that she regretted citing the case when she had not seen the medical record herself.“My daughter’s situation was exploited,” Heidi said, noting that the hospital told her that her records would be shared with the state.Missouri’s ban of gender care for minors will begin on Aug. 28 unless the hearing this week results in a preliminary injunction. If the law goes into effect, the clinic will not be allowed to enroll new patients.Some families are not waiting for the legal proceedings to play out. Jennifer Harris Dault, a Mennonite pastor, moved her family from St. Louis to New York in July to ensure that her 8-year-old transgender daughter could get gender treatments when she nears puberty.“The more I see coming out of Missouri the more I know we made the decision that was right for us,” she said.The attorney general’s investigation into the clinic’s practices is ongoing, as is an inquiry by Senator Josh Hawley, a Republican. While several families said they blamed Ms. Reed for the political fallout, others said the university bears responsibility, too.For decades, Dr. John Daniels was the sole endocrinologist in St. Louis prescribing hormones to transgender adults. He did so, he said, because he saw profound benefits in his patients and because, as a gay man, he appreciated the diversity of the human experience.When Ms. Reed’s allegations came out, he was shocked, and emailed her to ask if she had ever reported concerns to Washington University. She replied that she had, but was ignored.“I hate that the politicians have gotten involved with this, but I do have great concerns about how adolescents and preadolescents are being treated,” Dr. Daniels wrote. “That the higher-ups at W.U. didn’t take you seriously is now on them.”Kirsten Noyes

Read more →