When Politics Saves Lives: a Good-News Story

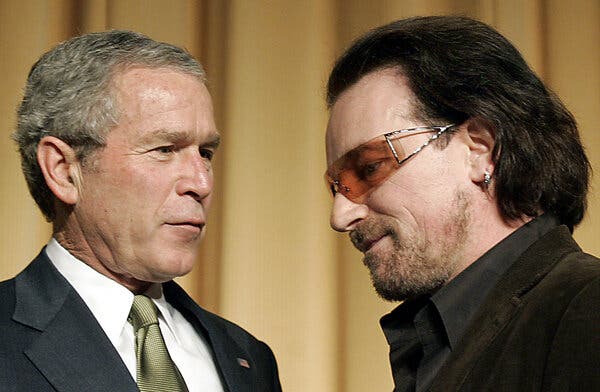

The decision to fund medications to treat H.I.V.-AIDS patients in sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean flew in the face of expert advice. But the U.S. did it anyway.President George W. Bush with Bono, the lead singer of U2, in 2006. Bono was among the activists who lobbied Mr. Bush for antiretroviral medications people in sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean.Jim Watson/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesHere is something I don’t write about very often: a situation in which unpredictable, seemingly irrational politics saved millions of the poorest and most vulnerable people on earth.In a recent blog post, Justin Sandefur, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, a think tank based in Washington, D.C., examined the record of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR. The program, started by President George W. Bush, paid for antiretroviral medications for millions of H.I.V. positive people in sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean, and is now seen as one of the most important foreign-aid efforts in American history, notable both for its generosity and its effectiveness.Setting it up at all flew in the face of many experts’ advice at the time.“The conventional wisdom within health economics was that sending AIDS drugs to Africa was a waste of money,” Sandefur wrote. It wasn’t that the drugs didn’t work: Antiretroviral therapy had achieved revolutionary results in controlling H.I.V.-AIDS, and had the potential to save the lives of infected people and prevent new infections. But the medications were extremely expensive, so experts believed that it would be more efficient to spend aid dollars on prevention instead. Money spent on condom distribution, awareness campaigns, or antibiotics to treat bacterial infections that made H.I.V. transmission more likely, data suggested, would save more lives per dollar than treatment would.In a now-infamous 2005 Forbes Op-Ed titled “Treating H.I.V. doesn’t pay,” Emily Oster, the Brown University economist who is now best known for her guides to parental decision-making, wrote that “as cold and callous as this may sound, after comparing the number of years saved by antiretrovirals with years saved by other interventions like education, I found that treatment is not an effective way to combat the epidemic.”She, like many other economic experts, assumed that policymakers were working with two constraints: a global health disaster on a massive scale, and a limited budget for addressing it. And because it was much more expensive to treat existing H.I.V.-AIDS patients than to prevent new infections, the grim conclusion was that to save the most lives possible, the best thing to do would be to focus on prevention — even though that would effectively mean letting infected people die.As it turned out, that argument was based on an erroneous assumption. In fact, the Bush administration was willing to find money for treatment that would never have otherwise been spent on prevention.The Bush administration had been the target of sustained political lobbying from interest groups and activists like Bono, the U2 frontman, and Franklin Graham, the son of the Rev. Billy Graham. Their reasoning was primarily moral, not economic, and they emphasized the plight of people who needed treatment. If antiretroviral medications existed, they argued, it was wrong for the wealthiest country in the world to leave poor people to die.So it turned out that the question was not just whether a dollar was most efficiently spent on treatment or prevention, but whether treatment or prevention would be the most politically compelling case for getting more dollars allocated. And on that latter question, treatment won hands down.Bush created PEPFAR, a new, multibillion dollar program to fund AIDS treatment in poor countries. And it ultimately not only saved lives, but also did so more cheaply than the initial cost-benefit analysis suggested. Over the course of the program, the cost of H.I.V. treatment fell rapidly — a change that may have been due partly to PEPFAR creating new demand for the medications, particularly cheaper generic drugs that came a few years later.Sometimes most efficient isn’t most effectiveWhen I asked Sandefur about the broader lessons, he said that sometimes an effective, easy-to-implement solution can be the best choice, even if it flies in the face of a cost-benefit analysis.“Close to home for me, working a lot on education, are school meals, which are, I think, fairly well demonstrated to be effective,” he said. “They help kids learn. They help get more kids in school. And they help with nutrition outcomes, clearly.” But programs like India’s midday meal scheme, which feeds more than 100 million school children each day, often come up short on cost-benefit analyses, because other programs are seen as a more efficient way to improve educational outcomes.Salience over scienceThe PEPFAR case also carries another lesson: Sometimes politics matter more than economics.The constituency for AIDS treatment included evangelical groups with a lot of political influence within the Republican Party. Having Franklin Graham make calls alongside Bono probably made it easier to get the Bush administration’s attention, but it also lowered the political costs of spending U.S. government money on a huge new foreign-aid program.In political science terms, saving the lives of H.I.V.-AIDS patients had better “salience”: activists connected with the cause emotionally, making it a priority for them.My anecdotal experience definitely bears that out: I was a student in that era, and I remember many passionate debates among my classmates about how best to get treatment for people in poor countries. I’m sure that, if asked, all of them would have supported prevention measures too, but that wasn’t where their energy was focused. The bulk of people’s excitement and urgency were focused on the issue of getting medications to people who would otherwise die. That felt like an emergency.So perhaps the bigger lesson here is just that policy is, at the end of the day, not divorced from politics. And that means that political costs and benefits will often beat out economic ones — even when that might seem irrational.Thank you for being a subscriberRead past editions of the newsletter here.If you’re enjoying what you’re reading, please consider recommending it to others. They can sign up here. Browse all of our subscriber-only newsletters here.I’d love your feedback on this newsletter. Please email thoughts and suggestions to interpreter@nytimes.com. You can also follow me on Twitter.

Read more →