Shunning the New Jersey suburbs in 1969, he set up a pay-what-you-can practice on the blighted Lower East Side and for three decades was a hero to the poor.Joseph Kramer, who tended to the afflictions of the poor as the self-described “country doctor” of Manhattan’s Lower East Side for nearly three decades, a period, beginning in 1969, when the neighborhood was infamous for urban squalor, died on Aug. 30 at his home in Leonia, N.J. He was 96.The death was confirmed by his daughter, Leslie Kramer.In the early 1960s, Dr. Kramer was working as a pediatrician in New Jersey’s prosperous suburbs in Bergen County and seemingly on his way to fulfilling the dreams of his youth — a red Porsche and a getaway in the Bahamas. Yet he began to find work increasingly unfulfilling.“It wasn’t that exciting; nobody was that sick,” he told The Bergen Record in 1990. “Doctors outnumbered diseases. Mothers would call up if their babies had a temperature of 98.9, or they’d ask what color vegetables to serve.” He felt, he later recalled, like “an expensive babysitter.”One night he got a hysterical call and rushed to a patient’s house, only to discover that the crisis had little to do with medicine. He returned home, called his partner and gave away his share of their practice.Dr. Kramer soon began working on the Lower East Side, where he had been born, and in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, where he had grown up. He set up his own Lower East Side practice, on Avenue D, in 1969, at one point early on offering his services to a woman with a stroller at a fruit stand. He wound up diagnosing her baby with club foot.Dr. Kramer in his office, where he treated 40 patients on an average day, including prostitutes, priests, bookies and Puerto Rican abuelas. Ken HeymanWhile his roster of patients grew, the neighborhood changed: Flower children and welfare-rights activists gave way to crack dealers and prostitutes. In the parlance of many New Yorkers, Alphabet City’s Avenue A stood for “Aware,” Avenue B for “Beware,” Avenue C for “Caution” and Avenue D — the last street before the East River — for “Death.”“The hippies ended up going to law school or working on Wall Street,” Dr. Kramer told The Bergen Record. “I’m still here.”He saw children with herpes of the brain, active tuberculosis lesions or wounds from being pricked in the park by discarded hypodermic needles. He evolved from a pediatrician into a general practitioner, treating prostitutes, priests, bookies, Puerto Rican abuelas and more.His office was in a converted ground floor apartment in the Jacob Riis housing project, where the living room served as a waiting room for crying babies alongside strung out drug addicts. He would see 40 patients on an average day. Many arrived with relatives who had their own medical problems. A fridge held the medicine. Kitchen cabinets stored medical files.He often accompanied patients to the pharmacy across the street and paid for their medicine, knowing they could not afford the drugs he prescribed. When one man with scoliosis lost his unemployment checks, Dr. Kramer paid for his treatments for three months.In 1983, a profile of him in New York magazine by Bernard Lefkowitz and a segment about Dr. Kramer on “60 Minutes” prompted a wave of news coverage depicting him as a lonely Sisyphus fighting urban decay. “On Avenue D, disease is not an isolated phenomenon,” Mr. Lefkowitz wrote. “It’s part of the social pathology of the neighborhood.”Twice while the “60 Minutes” correspondent Harry Reasoner interviewed Dr. Kramer on the street, someone came along and interrupted them. “There wouldn’t be no neighborhood without him,” one patient said.The New York Times described Dr. Kramer running a “pay-what-you-can-afford solo practice,” noting that he was the only private doctor in the 10009 ZIP code with hospital privileges.Dr. Kramer in 1996, the year he closed his practice. “It wasn’t the rise of AIDS, the spread of TB, the resurgence of measles,” The Associated Press wrote in explaining his quitting. “It wasn’t his 71 years, and it wasn’t the money. It was the paperwork.”Chester Higgins Jr./The New York TimesFrom under a bristling mustache he spoke in a Jewish street patois — hard-boiled sarcasm, loud cursing and, among friends, banter bordering on insult. Standing next to the children he cared for, Dr. Kramer, a broad-chested 6-foot-5, seemed a giant.Nicknames captured his intensity and good will. To a fellow doctor, he was “the Last Angry Man”; to a longtime patient, he was “the Guardian Angel of Avenue D”; and to the cartoonist Stan Mack, who depicted Dr. Kramer several times in Real Life Funnies, his weekly comic column for The Village Voice, he was “Dr. Quixote.”Joseph Isaac Kramer was born on Dec. 7, 1924. His parents, Selig and Frieda (Reiner) Kramer, ran Kramer’s Bake Shop in Williamsburg. Joe would pitch in as a cashier — resentfully. Sent out to run the occasional errand, he took breaks to do what he really wanted — play stickball.He earned a diploma at Boys High School in Brooklyn, graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1949 from the University of Kentucky, then left for Europe to find an affordable medical school that would accept Jews. He graduated from the University of Mainz, in Germany, around 1960. In 1963, he married Joan Glassman shortly after they had been introduced by friends.Dr. Kramer’s Lower East Side practice lacked a nurse, leaving him to devote hours each day, and every weekend, to filling out forms. In one instance, he requested $19 from Medicaid after spending 10 hours helping a suicidal young patient and got only $11. Continually enraged by what he saw as the stinginess and inaccessibility of the American medical system, he developed severe hypertension.He quit the practice in 1996, occasioning a final wave of attention from the news media. “It wasn’t the rise of AIDS, the spread of TB, the resurgence of measles,” The Associated Press wrote in explaining his departure. “It wasn’t his 71 years, and it wasn’t the money. It was the paperwork.”In addition to his daughter, he is survived by his wife; a son, Adam; and two grandchildren.Every August, Dr. Kramer attended a reunion of Lower East Side old-timers at East River Park. In a phone interview, Tamara Smith, a patient of his when she was a little girl, recalled hundreds of people swarming around Dr. Kramer as he entered the park for one such gathering — confirmation of his legacy as a “country doctor” who had treated generations of families.“He couldn’t even get off the ramp to get into the park,” Ms. Smith said. “He was every child in the ’hood’s doctor. I don’t know how he managed that, but he saw every one of us.”

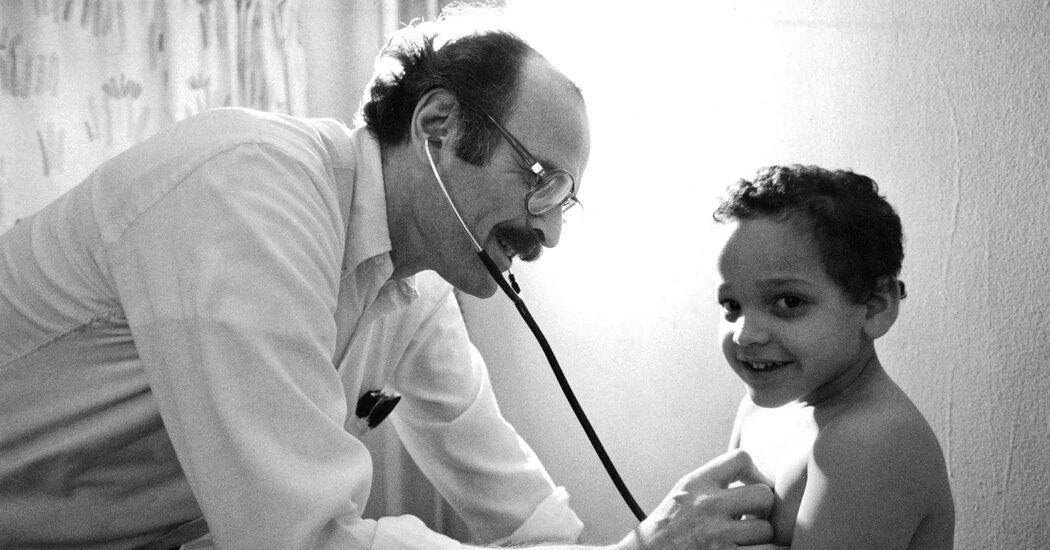

Read more →